toc

begin

bridge to bladensburg

STANTON PARK TO BLADENSBURG, NW

THE MAN SITTING NEXT TO ME is unexpected. That’s the point. Eight feet of bench affords the space. Magenta with a cool blue spine is an invitation — plus there’s something beckoning about hauling large, death-spiraling loads, this one full of splintered wood and bare, fox-tooth screws. It warps the gait. I looked like I could use the help.

I’d cut through Stanton Park and grids of yoga mats, where kids point and parents swat at their arms as if their children are pointing out the scoliosis of King Richard III. Up Maryland Ave and its arcade of interrogating smiles, one end of the bench plunked side mirrors and the other caught leftover holiday webs of the Capitol Hill gentry. The last half mile up the wrong way of 7th, the thing shifted in my arms and swerved me into the center of the street. It was easier on the road to tote it as a wrestler does a body before breaking its back, or like a banner before a ghost march, or the Human Feast loading its first mortal cache.

The cultural transects in this city are quick and welcome. I dropped the eight foot bench on the corner opposite an outdoor taqueria, took a seat, and immediately a woman named Tia sat down on the other end. She said she didn’t remember a bench being there. She gave me life and love advice in between drags of a Backwood roach. “Make bold advances before it's too late,” she warned — and then apply the test of a gas station flower. “Every woman knows a gas station flower. The plastic sleeve keeps them alive. If she still kisses you, she’s the one. Hold on for dear life.” I agreed without question, even if seize-the-day is always a suggestion for everyone else. I pointed and told her that the paint on this bench is still fresh, and as quick as a filmcut she tipped over to check her underside. It was dry and she slapped her thigh and howled up laughter to stop traffic.

I had to make it to Bladensburg. It must have been a wobble that brought it on: I felt the back end of the bench rise. “You’re good,” I heard, and I took up the front. In his free arm he carried a black jacket whipped around its contents. We lumbered six blocks before I suggested we rest our grip. We sat. Darren is from Florida. Been here two years. The hide of denim over his knees was slick as a burn. He said he was up for another six blocks of hauling. I had already told him I was going up the dogleg of Bladensburg — so I was in a fix. It’s an early principle of the Feast to warp a setting, to flex time and place in opposing thin mirrors, to go as far, or at least as far, to disturb the comfortable, but never to exploit — not much anyway, not six blocks of hauling a paint-gobbed, razor-toothed long bench, so I said I had time to kill, that the final resting place for this parcel doesn’t open for another hour or so. Darren said we might as well then drop it off in front. I was stuck.

The tree beside us, wreathed in chain-link fencing, popped off a scattershot of leaves. Big yellow, venous flakes rode down scallops of a swirling draft. One turned over on the sidewalk like a skilleted fish. I decided to tell Darren about the Feast. Those blue swatches on the back of the bench constitute a seal. I told him what I was up to, and what sort of particular situation this was. He stood up, looked at me, and said nothing. He circled around the side of the bench, tucked the cannon of his jacket under his arm, and grabbed the back end. I grabbed the front. We hauled the thing up Bladensburg. I researched my words. He must have supposed that we were actually delivering this long spine of painted wood to some speak-easy gallery south of Trinidad.

I stopped, and set the bench down. I reiterated that it was just part of some project, this unexplainable sort of questing that the Feast had made room for. But I can’t tell all it’s for. Regaining something we were forced to surrender. He said, “I know. I’ve got this end.”

~I.Re

Pre-Situ / the margins, Nov 3

the groove of history

“I CAME OUT OF THE SUBWAY, weak, moving through the heat as though I carried a heavy stone, the weight of a mountain on my shoulders. My new shoes hurt my feet. Now, moving through the crowds along 125th Street, I was painfully aware of other men dressed like the boys, and of girls in dark exotic-colored stockings, their costumes surreal variations of downtown styles. They’d been there all along, but somehow I’d missed them. I’d missed them even when my work had been most successful. They were outside the groove of history, and it was my job to get them in, all of them.”

~ The Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison

People

outside the groove of history: it is the politician’s job

to get them in, all of them, but the politician can’t do it because the politician has to hold his office in a withering plutocracy. It falls to the activist, then, until the activist grows jaded for asking everyone to stick around beyond the one big, staged event, the one concert or march. So it falls to the poet to sweep up. Without a poet, the only mirror anyone has is a self-portrait that can never last without being shattered by self-doubt.

Every living man and woman on earth needs a poet, someone who can write them back into the groove.

pre-situ / location, Nov 4

ghosts on the mall

INDEPENDENCE AND 6th

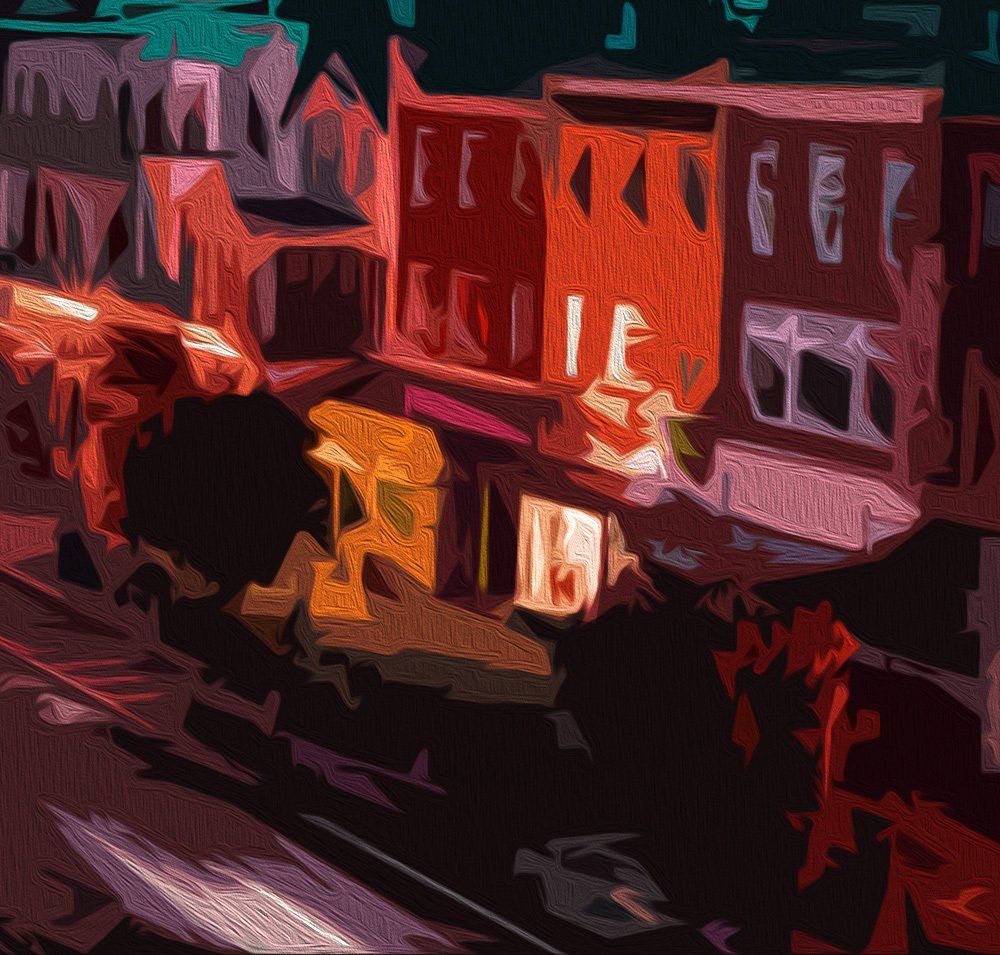

THE GRASS ABSORBS ALL FOOTPRINTS on the mall. Soon this sector will be full of protestors, but this morning couples walk the perimeter, or lie in above-ground plots and tell each other their winter dreams. The city of protest may have just become a fairground for a very specific simulation of civic exercise: The March.

I hope not. I don’t believe it has. It’s not some 21st century Renaissance Festival for marches of yesterday, not some old time portrait studio that serves up the Lincoln Memorial as a matte backdrop for your best protest signs and poses. Two years ago, it was Black Lives Matter. Two years before that, the March for Our Lives. Nearly two years prior, the Women’s March. And today? Today the grass is unpressed. It grows between frosts and marches. It is now accepting reservations for the next one. It is ready to receive you and your largest party of supporters.

There must be More.

Duchamp lamented forty years after his most famous museum incursion (a reverse art-heist executed by Banksy a century later) that the urinal he stuck on the gallery wall had become no more than an aesthetic object of art history. Does Martin Luther King Jr., standing over there by the Tidal Basin, lament the same for his March? Is The March just part of an inventory? Purveyors of postmodernism go even farther to suggest that The Protest March serves even the target of the protest, acting as an institutional release valve for public outrage, allowing a theatrical demonstration of moral indignation for One Grand Day before it disappears back in the office, the living room, inside the small screen of scrolling reports of speeches, reactions and repulses, back inside sports highlights, acrobatics and all death-defying, gravity-defying human feats and tricks you just have to see in video to believe.

Stand alone in the middle of this same grassy sector on the mall. Dead center. Arms outstretched. Look up through the interstices of frozen vapor and try to clear all of history. There will be bodies in tomorrow's march, but within them persons, too. They will have to be found.

~I.Re

under the flag

INDEPENDENCE AND 6th TO THE WHITE HOUSE

STERILIZE WITH FIRE, she said, before you extract the bullet: you must sterilize the tweezers first. Afra had agreed to take the call from her old classmate — the girl had initially texted but now she really, really needed to talk. She’d been shot in the leg at a protest in Tehran, and no one in the country could know. So she called Afra. The call switched over to video, and across an ocean two 16-year-old girls managed to pull off a minor surgery. This was four weeks ago, at the beginning of the demonstrations. With staggering naivety I asked if she then went to the hospital.

This is the fourth DC protest to summon attention to the harassment, abduction and execution of Iranian women by yet another interlocking piece of the world gerontocracy. A gerontocracy in resurgence. A renaissance of the old.

So some wisdom for all twenty-first century revolutionaries and incendiaries: listen to the girls.

This afternoon Afra was pissed — or at least indignant with the march itself for three reasons. Bring out your pen and paper, all brave and sympathetic protestors: These are rubrics of now this second installment of History’s Bloodiest Century.

First, she appreciates the support and paperwork filled out by the old vanguard, but it’s her demo now, her big subpop, her friends — down to the boy from a group chat who disappeared 14 days ago — who are “the impacted ones.” They’re the kids catching bullets Over There, so it would be nice to see more kids in the column marching down Constitution Ave over here. Stop watching in routine bouts of horror; flex the mirrors of time and place and put the counterbalance of bodies on the streets.

Second, a little more righteous urgency and anger, please. Afra thinks there’s too much fun to be heard in the clever chants around us. I tried to defend this spirit. I said there’s energy in anger that can be exuberant, liberating. A protest in 2022 is often more punk than any show. Primal screams for grievance and justice into uncompressed microphones, call-and-response by megaphones, dress and apparel that suit the message, and messages handwritten by vandal markers on torn cardboard. There’s an energy that’s diffusive, participatory and sometimes playful — real Situationist stuff. But as I was shouting in the swarm of it all, Afra said, “But people are dying,” in a way that didn’t sound at all as naive as what my explanation had become. I realized I was trumpeting the postmodern jubilee, part of the Big Show. Even the most revolutionary concepts, warns Debord, can be “emptied of their contents and put back into circulation in the service of maintaining alienation… They become advertising slogans… dissolved into ordinary aesthetic commerce.” It took Afra’s “But people are dying” to snap out of it.

Third, a little extrapolation, please. I asked Afra if she hopes to return to Iran in the coming years, if change comes. She shook her head. Too much homophobia, she said. Even at these protests she hears remarks in Farsi about her blue hair. If the headscarf is going to be pulled off for good, it will be pulled off for any style and color. Listen to your chants.

We had to get her under the flag. Afra wielded a pro camera. She was taking thousands of shots to send to her friends as postcards from a watching world. I suggested we could slip her under the giant drapery of a flag held above as a moving tile near the beginning of the marching column. We took to the sidewalk and twisted through parking meters and food trucks. Near Pershing Park a man played a grand piano for the oblivious consideration of diners who were blithely feasting on their freshly photographed food, a tableau of haute cannibalism. The giant flag finally passed us and we jumped back in. Afra ducked underneath and snapped some pretty great low-angle shots of marchers holding high the translucent drapery of national and anti-state pageantry.

Will she post these pictures on her accounts of a thousand-plus followers? She doesn’t know anymore. She’s safe, but her friends are not. The world gerontocracy has caught up to the power of the new printing press and hired the world’s best to repossess all apparatuses that had once promised to unleash the globe. That is, her photos might be seen by the wrong people.

I drifted down 14th street on a rented bike. Past a slotted-in march of Sudanese chanting to the same tune as the several thousand in front of the old White House. They were the size of a classroom, about 30 or so, mainly old men.

I sideswiped a police cruiser with my pedal. The gap was way too small, even with my feet up. The cop look galled but tired. I drifted south toward the monuments and slalomed through some construction cones. The air was cool. Couples walked northward in bubbles of cologne. I had just sideswiped a police cruiser in full view. Across an ocean, Mahsa Amini died in the custody of morality police because strands of hair were visible under a headscarf. Consider that: in fiction it would stretch the premise of any dystopian YA novel. There is no more extreme allegory to give.

The wars that will be fought this century will have to be wars of preposterous disproportionality. Over daily life. Over state-controlled apathy and constant distraction, boredom and escapism. It’s Afra against the world and its thickening shell, turtles all the way down, coming back up and piling on. It will take small, but persistent bending to keep some space free.

~I.Re

Post-Situ / Afra's story

why she protests

"

AWARE OF THE CONSEQUENCES, I played the piano on stage as my friend sang:

“City of stars,

Are you shining just for me?

City of stars,

There’s so much that I can’t see.

Who knows?

Is this the start of something wonderful and new?

Or one more dream that I cannot make true?”

Both of us started learning music as children, but we never had the opportunity to perform for an audience. When I was writing her monologue, I thought of every time I played the piano and she sang; we usually got yelled at. I didn’t understand why there was a rotting piano in the auditorium of an all-girls school where none of the students were allowed to play it. “What if you sang a song?” I asked her. She laughed and said no one would let us do that and we could get suspended. She was right. Women can’t legally sing solo songs or play instruments on stage with the presence of men in Iran. By performing City Of Stars in our high school, we were committing two different crimes.

The school admin asked me to remove the epilogue after our preview show. They said: “Parents will take pictures. The Department of Education will eventually hear about it and shut down our school.” I told them I would make sure no one took pictures, but they didn’t accept it. Neither did I. Although her monologue didn’t make sense without the song, we performed our first shows as they asked. Hours before our final show, I started asking actors and crew if they were willing to face the consequences of performing the song. The decision was unanimous.

I understood that the consequences would be magnitudes larger for the adults and our school. I chose to not tell our theater teacher. She couldn’t get fired for something she wasn’t aware of. As the writer of the show, I was next in the responsibility hierarchy. We asked the set crew to stand in front of the auditorium and ask the audience to turn their phones off and not take any pictures. We did it.

The applause was louder than usual. All I saw were mothers and teachers crying. After years of oppression, this was the first time many of them saw girls perform music on a stage. I walked up to our theater teacher. With tears in her eyes, she smiled and said: “Thank you.” I didn’t understand. I was called to the principal’s office the next day to “provide some explanation.” Surprisingly, the principal didn’t ask for an explanation. None of us were subject to disciplinary action because we didn’t cause any disruption, or maybe the administration wanted to pretend it never happened. She explained why I shouldn’t have done this because it was illegal, and asked me to not repeat my “mistake.” In a two-minute improvised speech, I told her that these unjust laws kill our dreams and someone needs to break them. I was willing to face any consequences and would repeat my “mistake” because I saw women cry for what’s been taken away from them. She told me that it was “out of her control.” I kindly asked her to keep the piano on stage. She accepted with one condition: I couldn’t touch it again.

Almost everyone pretended I hadn’t touched the piano – and I never did again – but the damage was done. Someone played the piano in every ceremony; I’d never realized there were so many pianists in my school. My classmates formed an unofficial choir – they occasionally performed at events but weren’t allowed individual concerts. Although I no longer attend that high school, I hear about my peers performing on that stage. I now understand why my teacher said thank you. Someone had to break those rules. It was “the start of something wonderful and new.”

~Afra

Malevich's Squares

INDEPENDENCE AND 12th

MALEVICH REPLACED ALL SAINTS with a big black void. He said he knew what he was doing. When his Black Square — regarded now as one of the most transformational pieces of the twentieth century — was analyzed for earlier drafts, however, it shows the usual prelim to uncorking something profound: screwing around with what will become. Doubt tears the limbs off of radical experimentalists. They sit on their back patios and listen to the chirrups of crows and think of walking a brambled path into the mountains with a bag of rice.

Maybe the Black Square in its imperial blankness did reset all of art last century. Maybe it negated everything preceding it with a punch to its own face. So now there are four Black Squares outside the galleries — there is no work easier to reproduce than the negation of everything; it’s just a black square on a large canvas, and we had the paint. We sat on a patch of stools on the Washington Mall, watching four black squares flap and tip over in the wind. We mused. The Black Square near the end of 2022 is not just a negation of all preceding centuries, it is a faithful composite of this one. If all art had been reset to what it could be, which is anything and everything, then from that act of consummate destruction all art that could happen did happen; in genre, subgenre, cross-genre; in grotesque, baroque, and burlesque; in minimalist and in white noise. Now overlay everything, place everything on top of itself, automate it, and we crunch back to the Black Square: all art mashed together on one single canvas. We live in that space now.

So there are four Black Squares catching the wind on the Mall on a cool autumn day. Ice cream trucks along 14th play their infernal carnival rotations in chiptune disharmony — someone should check the actuary tables for ice cream vendors indexed by violent crime, because we're sure they've been attacked for their infernal duplications of the same tune.

The Black Squares keep flying off their stands and I keep resetting them, and each time it’s an interruption to our conversation about the Black Square. I look down the mall. Three grids down I can make out the convening spot for all of last week’s protests, all those pictures of victims that look like composites of pictures of victims in all previous protests.

Make that three Black Squares. I’m not picking that fourth one up again. It’s flown some distance and there it’ll have to wait. We’re in the middle of a conversation. We had wondered if anyone would engage with the squares themselves, but most just smile and regain their channels in the pebbled walk. The younger elms down the sides keep hold of the greener leaves; in the city, leaves change and fall off weeks later than in the mountains. It’s nice, honestly. Later we’ll all check out the Hirshhorn and see what linguistic acrobatics contextualize the repeating phalluses on the walls. Most settle with the word “evocative.”

A family approaches the three remaining Black Squares. Dad is eating an ice cream cone. One of his sons spots the fallen fourth square. He runs over, arms straight and flickering the way young kids run. He picks up the canvas at the corner with his grubby hands. He balances it in the wind, and walks it carefully back to the stand. He places it, adjusts it, steps back to assess, and then returns to shift it a little more. He walks around to the back legs, and he adjusts them with his little hands, too. He steps back and examines his work. By god, if one eye isn’t shut, and then the other, measuring like a mason. All the squares are symmetrical again. They vibrate beside us with all-consuming energy.

~I.Re

Pre-Situ / this is the day, nov 8

the monster mash

I’VE WONDERED IF THERE'S MORE Debord in you, or Vaneigem. Debord is of the manifesto type, a utopian who knows better than to try, but can’t help himself. He hears the din of a crowd and immediately erects a scaffold that extends too high to climb or to hang anyone by. The scale is always too much: a revolutionary’s paradise is only held together by the opposing tension of the monstrosity it seeks to destroy. Debord must have known this, that to the revolutionary the crushing forces of society are as essential as a brick wall is to graffiti. Vaneigem, however, lived by it. In fact, Vaneigem, the radical lover of the group, knew that love itself depends on monstrosity: What fun is it to run between curtains and walls of ghosts with just one other fully alive person? I'll answer that. It is serious fun. It is love. While Debord sits high on his scaffold fixing ropes, Vaneigem is down in the mortal mash, dancing with the living.

The sense is that when Debords come together in combination, Debords with Debords, they become Vaneigems. Revolution is not some distant state, but rather a night out, a trip to the grocery, a walk to riff off each other and devise some bright new theory of space or expand upon the magnetism of the Curies. To the revolutionary, every single morning is a birthday. This heightened awareness becomes a permanent fixture in any affected soul. For Vaneigem and his colliding planets, no matter the phase or eclipse, or the height of the scaffold, the teeming mash around us will always look different. It is a deification first sought in a place and a people, but can only really be found in a single person and a shared experience.

In his garlanded “Revolution of Everyday Life,” Vaneigem embraces the forces arrayed against him: “From now on, no one can escape the need to conduct their own investigation into the criminal racket that pursues them even into their thoughts, hunts them down even in their dreams. The smallest details take on a major importance. Irritation, fatigue, rudeness, humiliation… Who profits by them? And who profits by the stereotyped answers — really just so many excuses? Why should I settle for explanations that kill me but I have everything to win at the very place where all the cards are stacked against me?”

For Vaneigem, for us, the rigged game is a field of play. You can hear Samuel Beckett’s absurdist culmination,

it’s just play, but instead of hitting the button on talking heads teetering on urns mouthing their daily quota of gibberish, it’s us playing in the background din, making music out of everyday noise.

And that’s where we find you are most alive in your skin, at

play. That’s all we’ve really wanted from the start. That is the morning that is a birthday.

~I.Re

they bear forks

ADAMS MORGAN

YOU MUST NOT LOOK like a jogger. So flay off the mid-thighs and mannequin polyester blends. You’ll need working clothes, whatever that means, probably something in buttons. Nothing tucked in or tidy, though. Boots not trainers, soles that are flat and clap at the street rather than keel over like a couple of waggling dough pins. You’ve got to run, you’ve got to tear up the street, up along the sides, criss-crossing lanes and cannon-balling over bumpers and concrete barriers. It’s a sprint and it should feel like heaven’s trajectory out of hell. There are stretches past the hookah and smoke shops, the bakery and the Tibetan bead shop where the whole torso’s ribbed up and riding high on oscillating legs; it should feel like you're coming out of the sea. It’s a coursing, the road’s moving like a belt, the falafel shop is falling down the sidewalk, and the mash of feet is tearing back the skin of the planet.

You must run like you’re being chased. Because you are. This week was the last election. Everyone’s rapt in numbers, grazing, throwing watch parties to the undead and waiting for the shelf to collapse in the middle of the Atlantic. Everyone’s watching and walking things. Walking to shift nodal points in the human matrix for a faster replicating strain. Watching for slings and arrows — those daily insults, humiliations, and libels; they’re digitized now and replicating faster, and some of them will inflict maximum damage and unsaviored crisis. It’s now life-threatening to know too many people, and for too many people to know your name because they might use it, contort it, implicate it. Just one cut and the forks and knives are out, and everyone’s flashing their teeth at the table. Flat on your back you look up and see some familiar faces. The tines of forks twirl in your hair and tug at your shoelaces.

You’ve got to run, and for the life of you, you’ve got to outrun the specters of algorithmic doubles and the statistical proof that there are thousands exactly like you, interchangeable and replaceable. It’s the first time in history that the notion of self has been consumed by billions tied together by machines assigned with finding and amalgamating types of people, and to our horror, it turns out they’re not that many. It’s the first time since Goethe proclaimed the supremacy of self in a small German town 250 years ago, since the revolution of self and individuality has been simplified and pared down to library posters and pop songs. It’s always been a fundamental part of lore that if you should actually

meet

your doppelgänger, you’ll lose your mind. Now we stew and evaporate in cybernetic groups of our identical selves.

So, yeah, we’re being chased.

So you run like mad. You run to leave your heels behind. You rip past walkers and in between stopped traffic, scraping past skids of boxes and hurtling over barricades and through gazebos the pandemic built: this, on this particular Tuesday evening in Adams Morgan, is your quarter mile Sabotage.

I clipped a barrier with my hip and swerved into Shenanigans, but couldn’t trust the name or the century the pub clings to, and ducked instead into Julia’s Empanadas. It’s a perfect alcove of a window bedecked with two seasons of pumpkins and sunflowers, all lit up red and blue by tilting neon light. The Feast made this chase so I ducked in quickly and looked out the window. “Everything all right?” a woman, maybe Julia herself, asked behind the counter. “Everything’s cool,” I said. “I just can’t be found right now.”

The place was empty. It’s tiny in there. She walked out the door and into the middle of the sidewalk. She squared off and looked south. She used a dish towel to rub clean each one of her fingers, inspecting them and looking down the walk. She came back in and said, “You can stay as long as you need to.”

I checked through the window. There’s a scene in

Tombstone

where Wyatt Earp drops off a twice dying Doc Holliday at the Henry Hooker ranch. Dark brown horses against a gun metal sky, “Hooker rides up, strong, noble-looking, like something from a Frederic Remington canvas.” He tells Earp, “Cowboys or not,

you can stay here as long as you want.”

I picked out a fat coconut and pineapple empanada. We talked about sunflowers and their housefly eyes, and the remarkable possibility of resurrecting plants by a single leaf cutting. Maybe this is how the world restarts.

Later I dined on the pastry over the railing of the Connecticut Avenue bridge. Below, in the dark of Rock Creek Park, I could make out tiny globes of tumbleweed trundling down the dirt paths and road, hurrying somewhere.

~I.Re

Pre-Situ / in the park, Nov 9

hear it out

ROCK CREEK PARK

"In an age like ours, when people are assaulted daily by the most monstrous things without being able to keep account of their impressions, aesthetic production becomes a prescribed course. BUT ALL LIVING ART WILL BE IRRATIONAL, primitive, and complex; it will speak a secret language…"

~Hugo Ball, 1915

So there’s fun to be had, especially for the eternally hungry, especially for a mind that must feed. But you’ve got to court the thing calling outside. You’ve got to hear its wail just over the ridge. You’ve got to go to it, and you’ve got to listen — because its logic not only dwarfs sense, but outlasts it by two centuries.

Even more so, you’ve got to hear it out because you know, more than you know anything, that you are its equal, and it is yours when you say, "come here."

Situ / A situ found, Nov 10

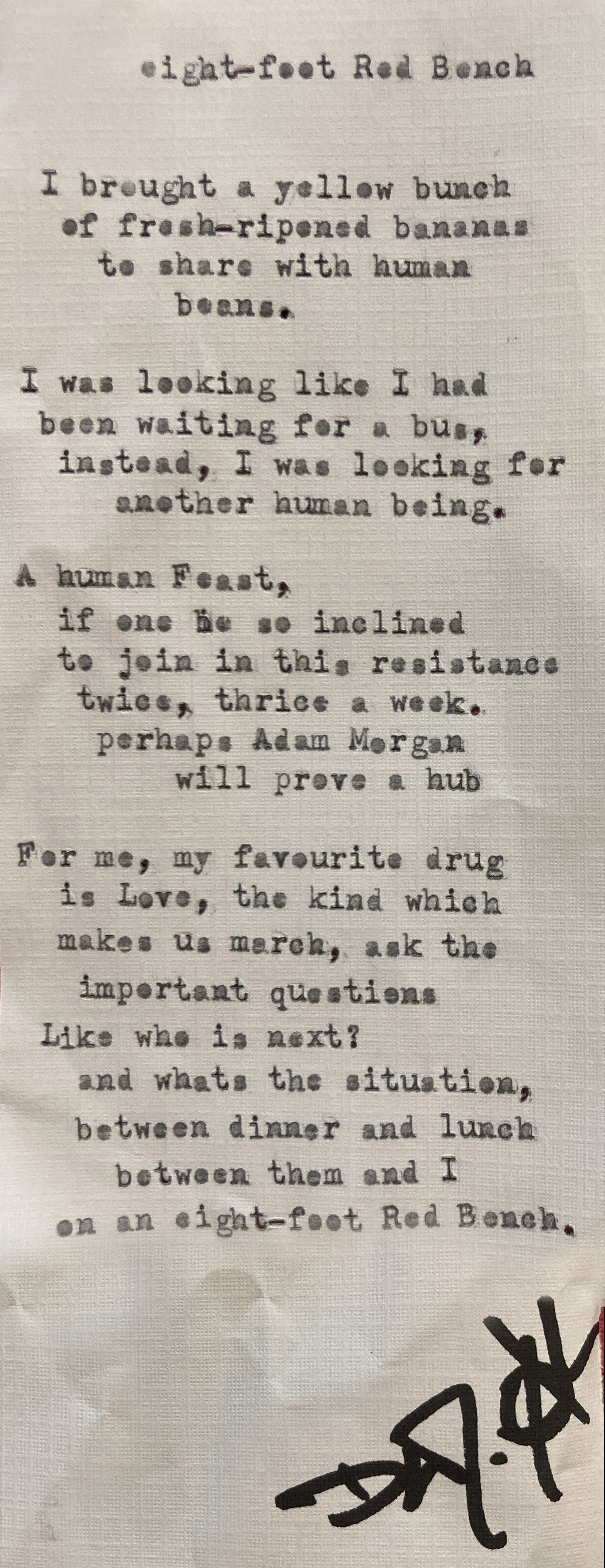

street poet

ADAMS MORGAN

IT'S THE SORT OF LOOK afforded a man in the middle of giving chest compressions. A few punches of ink by the old type bars and people rock a stare that would land them in jail once eye contact is considered assault. It’s fine, though, even lovely.

We’re busy talking. Or at least I’m talking on and on about The Feast, about media-induced imbecility, about pathological boredom and the need for more portable red benches across the city, and the Poet is busy typing. He’s set himself up on the sidewalk in front of Lost City Books asking questions, listening, and typing on the keyboard of a vintage typewriter, with an old copy of Ulysses counterbalancing the small table. He is a stenographer of hidden truths. What passersby are looking at, why they cock their heads and smile their hungry smiles and issue their uninhibited stares, is not because of the old device or even for an ancient art, but for a niche in their memory for something they were promised as children: time for play, and words that encapsulate all they need to know on any subject.

Poet:

D. J. Allen

headless and alive

9th and U

A FIFTEEN DOLLAR SHOW. This is important. The higher the entry, the more removed the audience. Participation — which is a less philosophical but duplicate term for free will — is pure fantasy in large venues. This inverse proportionality applies to any setting; critical masses must be managed so bodies don’t pile into a clot. Traffic flow, road design, security gates: all move human material across a slick honeycomb grid. The reason automated driving estimates are so precise is because it is only human material that is being moved, completely lopped off of decisions. Lane widths are studied and manipulated. Stadium-seating warehouses the human stock. There are queues and zones. It’s all efficient, but also all behavioral: every city council knows that hooliganism is drained off by routes and timetables. Like an embalming, the material all sloughs down troughs in opposite directions.

Here now she stands before us in a small venue, Marie Antoinette recapitated. Swaying, held in place by the guy-wire trance of a few deliberate eyes. It’s a sort of opening dirge that she moans, which makes everyone restless for an escape rhythm. There’s maybe twenty on this small dance floor? At DC9 the stage is only inches higher, egalitarian, intimate as a basement or punk debut in a school cafeteria. DC9 has usurped the spirit of the 9:30 Club on the other side of U-Street, and the whole IMP Concerts-for-Condos Empire. Now it’s DC9 that captures bands on the way up and down their career trajectories. Slaves UK played here a couple of years ago. A Place to Bury Strangers rejected the stage and played in the audience; come to think of it, Slaves played on the bartop.

We’re just waiting for the body of Marie Antoinette to go off. She’ll flop to the floor and scream as her custodian slashes at a drum suspended two feet above his shoulders. Cables hang as tendons and circulate the witch-croon melody.

We’re just waiting. To my left stands a woman named Lara who drifted up from Lorton. She told me she’s been looking forward to this show for weeks and how good it is to “finally be with real fans,” though no one seems to know how to pronounce the band’s name. Up on the right is shifty-eyed Nate. He’s young, already perspiring in a black and red striped sweater, and is constantly looking around for behavioral cues. Behind me a tall girl has peeled away from her friends sitting in one of the back booths. She’s either really tall or tall on top of platform boots. Eyeliner extends from the corners of her eyes and an anticipatory smile belies the anger of her black Misfits T.

The intro ends in a consensus beat — we all agreed this would happen, but it’s just a high-pitched, cracking snare. There's no bass or rumble so everyone seems caught unaware. Is this it? Does this set us off? Nate’s eyes are twitching everywhere. Irrespective of the absent bass, it’s time. I begin to hop. It's an anticipatory hop. Half begin to hop along, too, but it’s all on promissory notes; we’re building latent energy into the system. Some close their eyes and nod in trust that the heavy beat will come. Antoinette looks over at her man. He bends down and searches for a dial on a foot pedal apparatus snaking across the stage. He flicks it and turns it over. At once a bass gurgle washes over the room, and those of us already in the air are ensconced into the groove. We hop and ping off shoulders and Tall Girl is laughing. Nate’s black, curly hair detonates in the scattered light, eyes closed.

Marie Antoinette flops onto the floor between us. It’s that part of the song. Do we pick her up? She’s very deliberate. Her band mate makes the decision and rushes forward to pull on her bare arms. We help gingerly because hair and corset are intertwined and there are only a few spots for acceptable finger holds. The batons that had been striking the overhead drum have been put down — and still the beat goes on. It’s unclear what hand motivates the music, but in a club this small, for a band this rough, it’s pretty clear it’s us.

~I.Re

The city we want

Dupont Circle

THE HARDEST SELL lies in convincing people that we're selling nothing, that even in this neighborhood there’s no exchange. We chose paper notebooks instead of clipboards or electronic tablets, and we kept it messy, though there needed to be a little decorum; we didn’t want the public to think we were insane or, worse, that we were grad students. We work — we told them — for a small group called The Human Feast, and we are collecting ideas to improve the city. This introduction came second. The question came first: Can you tell me what this city can build for you?

Most remained suspicious. It’s been a prevailing metaphor of this movement that the bulk of people have come to regard each other as dollops of flesh, to sup anxiously on each other’s stores of energy, and that in every exchange there’s a transaction taking place, the siphoning off of souls in allotments of pennies and dimes. Besides, it was too open of a question, and their education has not prepared them for the blue skies of sudden conversation. I said I would give them thumbs-up / thumbs-down questions. Likes and dislikes, and for this match they were prime.

First question: Should the city plant more trees and more gardens on the national mall? How about sections of pine forests, apple orchards, and willow trees with long wooden swings hanging from the branches?

91% in favor (74/81). It was the swings from giant willow trees that opened their eyes to possibilities.

How about long, flowy hanging gardens down the faces of all federal office buildings, with ivy and pothos dripping from the cornices?

61% in favor (49/81). Some description of pothos was required. Some wanted to know who would take care of it all.

Converting the 14th Street Bridge into an inhabited bridge, where local shops line the periphery: full of flower shops, rare book shops, juice bars and record stores?

77% in favor (62/81). This required a brief history of medieval bridges. They liked the juice bars most of all.

How about floodlights to wash over all monuments with color, the hue determined by the weather, by temperature or the likelihood of rain?

50.5% in favor (41/81). I explained that the Jefferson is most alive in the early summer glow of scattered storms. I’d seen it with my own eyes; I’d seen it through another’s eyes. They remained split, though. They weren’t sure about colored lights synced with the coming weather.

Speakers that are installed and hidden in city squares and traffic circles, such as Dupont and Logan, with free online reservations for requested songs?

49.4% in favor (40/81). People loved or hated this one, polarized. The results were beginning to look like an election.

Opening up the city’s cemeteries to picnic grounds?

20% in favor (16/81). I pressed in vain on this one. I said it’s a matter of historical belief systems, mostly stemming from a Puritanical culture of mourning. But is total abandonment a sign of respect? Consider picnics in cemeteries. Instead of ostracizing the dead to their cold, barely seismic dirt, we’re there among them, chatting about our days and eating chips and dip. Imagine the nature of outdoor picnic conversations, with the dead listening, and the dead imploring, too... But this may have hurt my case. No one wants to listen to the imploring dead.

How about this, then: A baroque opera house, busted open, with open doors, open windows, and a partially covered roof, to replace the big white brick of the Kennedy Center?

27% in favor (22/81). There remains love and honor for the big white brick. This question also was offensive.

All buses converted to psychedelic Indian buses covered in bric-a-brac, greens and yellows, circles of mirrors and icons of local legends who should be canonized, such as Duke Ellington, Chuck Brown, and Ian MacKaye?

33% in favor (27/81). Much explanation was required, the nature of bric-a-brac, religious iconography, and the identification of those people. Most wanted buses to stay city buses, sleek and slathered with ads for health care. For those 1 in 3 who loved the idea, I felt an instant kinship. Secret smiles between us.

They were now primed. Blue sky. What do you want to see in your city?

“More parking.”

“Cleaner.”

“Less trash and fewer homeless.”

“Winning sports teams.”

“More security systems.”

“More fun structures to take pictures in front of.”

“More statues.”

“Statues of me.”

“More animals.”

There is a distinct inverse proportionality between age and the lust for change. The younger they are, the more aesthetically conservative. This is surprising. Only from the young came the questions, “Who will pay for this?” “Is it safe?” “Won’t it cause more traffic?” “Isn't that dangerous?” “DC needs to do something about its criminals first.”

The young are most worried about “the criminals.” About the specter of imminent danger. The fantasy of marauding gangs in all other quadrants.

And that there are far too many homeless.

That evening, south of Dupont, I sat on a curb with a man named Leon. He was a large man and said he had a big appetite. I gave him a ten dollar bill. With that transaction over, we sat there and watched the slush of people slope downward off the circle. Once Leon noticed I was sticking around, his voice changed. His sentences grew longer. I skipped the questions and asked him what the city needs. He thought for a moment, laughed, and said, “softer sidewalks.”

~I.Re

post-Situ / in the margins, Nov 13

home of golden looms

"HERE ARE TO BE FOUND 'Pits of bitumen deadly', 'Lakes of Fire', 'Trees of Malice', 'The land of snares & traps & wheels & pit-falls & dire mills'. Yet if you can shake off the dust of the earth, 'whatever is visible to the Generated Man', then you may approach the great City of Art and Manufacture where every lovely form exists in fourfold splendour. Within the courtyard there burns the moat of fire protecting Cathedron, or the home of the golden looms, which weave all created things and in which 'every Human Vegetated Form is in its inward recesses'.”

~Blake, by Peter Ackroyd

Give us not a clean city, scrubbed and straightened. Give us moats of fire. Give us city misdirections that become gilded boulevards while the city sleeps. This is the city we want, and the person, in fourfold splendour.

pre-Situ / on a stoop, Nov 14

conversation with a stranger

I SPOKE OF ITS PHASES, its tidal pull. He, no longer a stranger because we shared this space, a stoop in the city, reclined back on his elbows and stared into the sky. I resumed with theories of its origin, from the slow accretion of impact debris into a compact ball, to its abduction from Venus. He stared, and so I went into a survey of its mythology across cultures and time, at least the few that I had remembered, and ended with the general sentiment that it makes its adherents stark raving mad. He narrowed his eyes, and asked if the moon had a ladder.

Xitu / small Venue, november 15

blue note

Soft Moon at the Howard Theater

HE SAID WE COULD NEVER KNOW what hell it was to sing these songs. What do we do with that? Do we picnic in his cemetery? Do we dance?

It is an effigy of a venue. No vibe seems to fill the volume of Howard Theater. The air never parses the light. Its creatures seem to live in panic that someone will turn on the main switch, and then we’d all be caught. With its glossy parquet floors and clean interior, there’s this sense that someone came up with the wild idea to book a goth band for a wedding.

Do we dance? He held his face a half minute before unstrapping the guitar and lancing it through the backstage curtain. He lunged for the microphone. The intonation was so grim and strung out across bars of the primeval beat that maybe the despair was performative. Maybe in the photographic age, in this spectator age, all emotion is performative. Children see the contortions of a sad face and swipe at it with their thumbs. The despair we see on stage emotes as much as the faces we watch through glass. Besides, once the bongos were brought out — bongos! — and blended into the refined oily mix of programmed percussion and a genuine drum, the question was answered. Black hair, sleeve straps and coiled fists stamped the flickering strobe like typewriter bars, and whole pages were written in the space of a set.

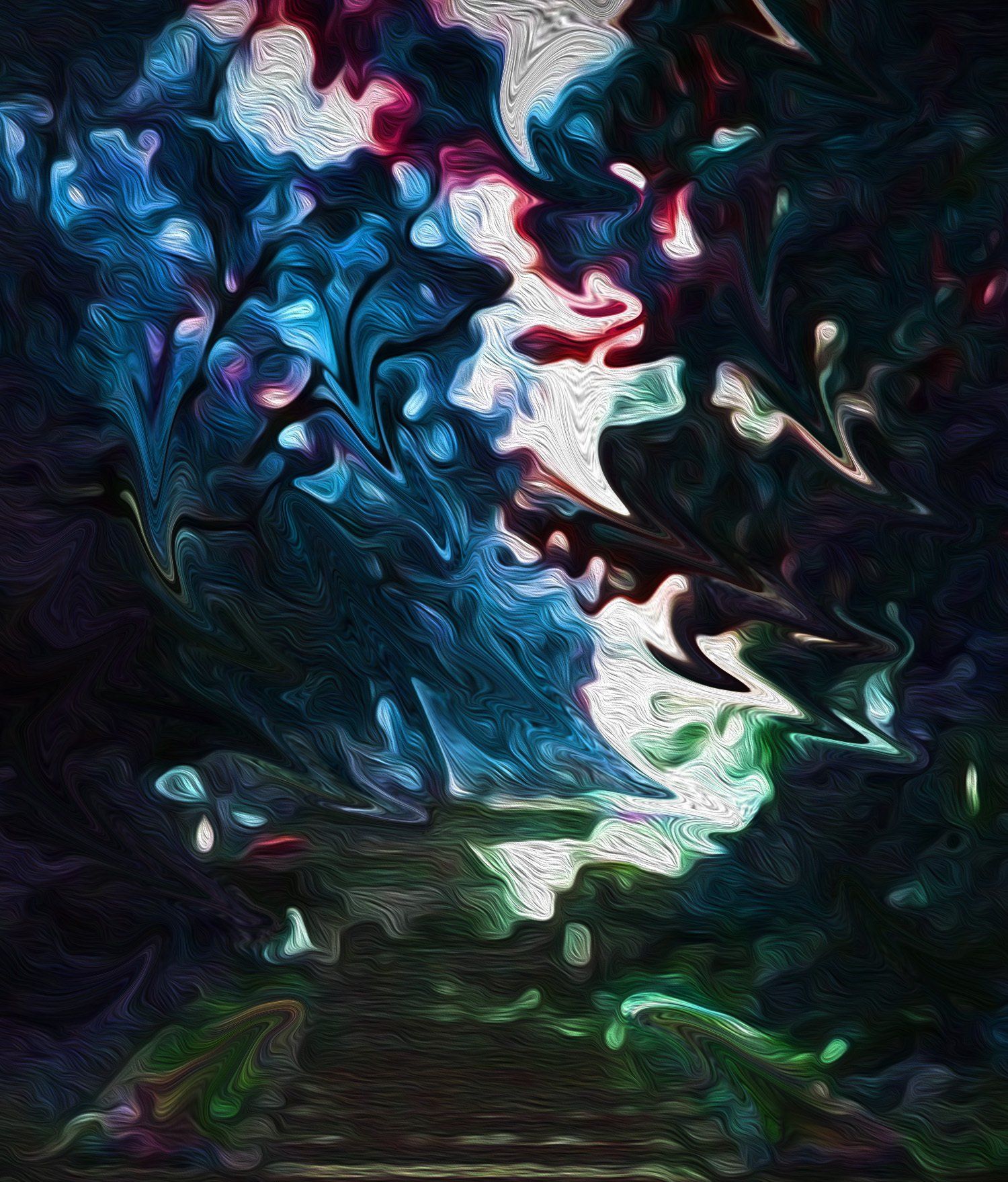

There’s only 35 in the audience tonight. Each one came alone. Everyone hopped, nodded or stood in plots of their own, equidistant from each other, tent poles holding up the small-top circus. Halfway through the set, curls of fog filled the front half of the club, emancipating the space from its sheer utility. Blue light woke up and latticed the ether. We stood at attention and I froze a bit at the childhood memory of reading passages from the Book of Revelations. This is how I saw it. Bodies risen from their plots and standing at attention in the murk of blue light.

Everyone had come alone. Everyone left alone in six foot intervals. Had I not noticed this before? Was this new? The atomization of night club audiences, too?

The history of art and music is undergirded by stories and declarations of anti-establishment defiance. This may be the beginning of a time where showing up at all is in defiance of ourselves. We must stay out. The future of the human race depends on it, sharing the same beat.

~IRe

A RETORT WE RECEIVED ONLINE:

In Revelation, should old paint peel from the walls, and heavenly spectator's shoes stick to a gummy floor, I think no one would notice. Is the Howard Theater's converse incongruity of attendees and venue any more significant? Or is this the artists' imposing a stylistic construct on this particular human feast?

~ Searcher

There is a construct, but the construct

is the incongruity between venue and attendees. Place must bend for people; it must allow itself to be reconfigured every night. Place should feel like now, rather than history. Paint should peel from the walls in curlicues and ribbons every night. The revelation is that we've been evicted from the present, written out of the groove of history, and made spectators to a process that was completed and automated when we weren't looking.

~Feast

pre-situ / prospects, nov 17

who opens the gates

A BODY SWAP will open the hidden city tonight, if bodies are chosen carefully. If too tidy, if they carry satchels in their hands instead of bags slung over their shoulders, if the toes of their shoes come to a point, if in suits, if they check the hour, if they look mildly pained at this portion of their day, they will lead to nowhere. Those bodies only tread a flatline between evening necessities, between finding shelter and food and back again, pinballing through all the tokens of their leftover days. Maybe they have a trip planned in the distance, but tonight at their reserved tables they’ll have to work up the energy to say what’s already being repeated at the next table, and chunk together the phrases of the broadcast voices in their heads. The phrases and tokens of forgettable news events for a national audience. That energy, too, will dissipate in a static of diminishing returns. Their material has run out. They are undamaged, unwritten, plotless... They will lead nowhere tonight.

Give us instead moats of fire, misdirections. We look for damaged bodies to lead us to places we didn’t know existed.

all hear voices

THE BODIES TO FOLLOW TONIGHT do not rush. They investigate breakages in the fencing, they return to streets they’ve just descended, inexplicably, and disappear down another. You have to be cagey. They wear loose boots or scuffed joggers and knit caps. I swapped a body that trained a line of blue smoke for one that wore shorts over winding tattoos on a 37 degree night. I swapped that one for another bagged to the knees in an oversized hoodie, straight down to a cluster of tents just north of the Kennedy Center.

On a concrete rise I sat with a family of three. The stroller was covered in a zebra-print canopy. We watched a man swear at another man. “I want to hit you so bad,” he testified as he ripped off his coat. I wondered where this would go, but everyone seemed unimpressed. He donned his coat again and marched to the edge of the street to enumerate his grievances to passing traffic. He came back. He ripped his coat off again. He declared what he’d do, the carnage he was capable of, all the anatomical edits and revisions he would make to the man he'd make his victim, the dismemberment, the total perversion of the man's body and soul — but again he stopped short. He returned to address the road, speaking with all the candor of a fifth-act soliloquy. He rushed back to describe in even finer detail what he would do, and what he would do at this very moment if he weren’t “on paper.” We didn’t know what this meant, “on paper.” It wasn’t until he returned to the street, swearing, that he swore something about parole. "On paper" for 22 years. Is that possible? Before we could deliberate he returned again and tore off his coat again. I said, “the man is running on a circuit!” and the mother next to me — Julia — laughed, “he is!”

When finally he broke his pull string and left for good, the man who was supposed to be his victim, a skinny one in a parka, stood up, took a careful breath, and began his turn screaming. Every single charge that was given to him, he now had the perfect answer. “They’re pretty good,” said Julia about his retorts, each one of them screamed in vacancy.

Behind us an old woman sat in a niche of the backing wall. She told me she needed to go shopping for Thanksgiving. She cooks for a couple homes nearby. I asked her the best way to cook a turkey. She uses corn bread and cheerios as stuffing, with milk and eggs. She bathes the turkey and uses her hands to butter every stretch and wrinkle. The seasoning — “that’s the accent,” she said — is a tincture of honey and brown sugar. Her name is Pearl.

I followed a body with what looked like a lost and found fireman’s jacket, mottled with strips of reflecting tape, all the way back up to 18th Street. I was surprised to see that on the corner of Columbia and 18 everything had been stripped clean. Only days ago the fence and walls around AdMo Plaza were covered with posters protesting the takeover of the public space by Truist Bank. They have big plans to build a luxury condo on the site. Last spring Truist fenced off the space and destroyed the tents and property of people who had taken refuge there during the pandemic. It was the first time the space was closed in 45 years. All of the protest posters had been cleared, only leaving phantom strips of adhesive in their place. All that remains is a portrait of Miguel Gonzales, who had frozen to death a couple weeks ago because his tent and sleeping bag were trashed. Perhaps the clean-up crew resisted that one order; the portrait stays.

The public square is still populated. People sit on concrete barriers and prop themselves up against the fencing with words to spill. There’s something redeeming about this. The barriers that were designed to keep them out have been turned into benches. To Truist Bank, the perfect city is one stripped clean of people, but people will always be there. They have to be, sitting on its barricades, mothers and grandmothers with accents of honey and brown sugar.

~I.Re

straightline

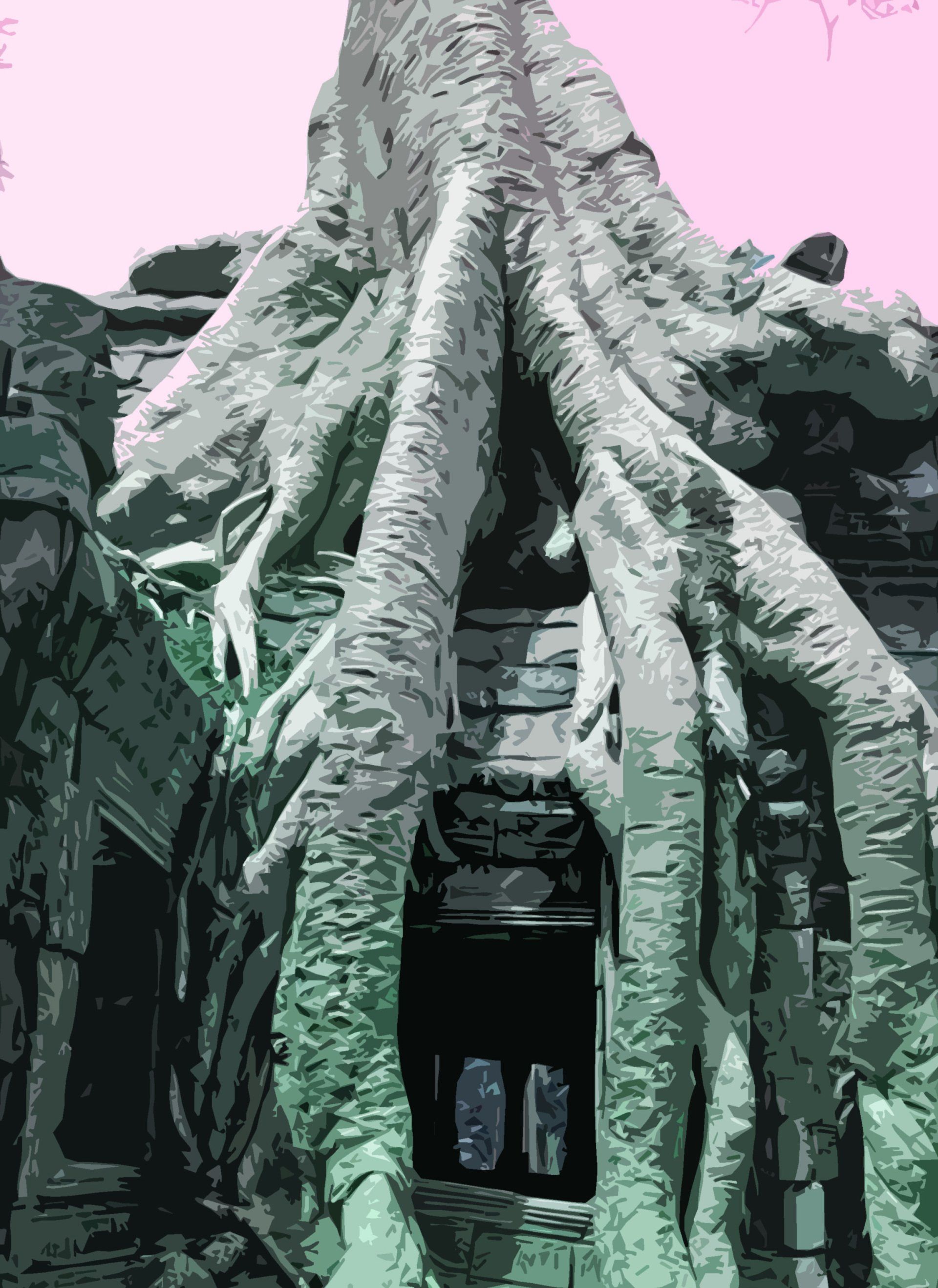

TO STRAIGHTLINE A HIKE in the woods is to spite all thorn patches, rock walls, and snares of vines and roots. It’s to spite all trails and Robert Frost himself. It’s to stand in the middle of the road and point to some unlabeled summit and go there directly, no switchbacks or meanders, just straight to it. In the city there will be fences to cross, trespasses, dog yards.

The straight line I drew on the map was from the yonic gardens of the Hillwood Estate to the steps of the Basilica. To walk a straight line in a city is an aggressive act, a straight line deviance to spite channels drawn for behavioral compliance, but also for compliance to aesthetic principles. Ordinarily, you are to see only what you are led to see by the routes you walk and the maps you follow. If Orwell warned that all art is propaganda, so are maps, and so are sidewalks.

I started in the leaf litter of the eastern, barbwired slope of Hillwood, the enlightenment principle of symmetry ringed in by blood-drawing wire. The Basilica is east-southeast of here, so I pointed a compass in that direction, marked a crooked tree in the distance, and started. Across the Ridge Trail and its sentries of joggers and down the bank of Rock Creek, there was a decision: a fording of the broad creek. Shoes off? It’s cold, and that cold will stick if drenched and sucked to skin, but the Basilica is only three miles from here, and I liked the idea of reaching those steps as a proper pilgrim, with a cache of mortal sins and two cold, wet feet. Shoes shall stay on for the crossing.

Across Beach Drive and immediately up into the thin strip of National Park land, the trees in November are stripped white. I hit the base of the crooked tree and marked by compass the next one, across a valley, traversing a trail with a sign posted for a lost labrador. There’s a drainage at the bottom with a twee wooden bridge, but it’s too far off the line. Instead a fallen trunk, its ripped-out roots radiating upward like a painted sun, fits the line perfectly over the little ravine and its crease of black water. On this slope invisible to traffic there are three tents, green Kelty tents with bouquets of shiny pinwheels sticking out of the vestibules. Outside, there is a tidy row of shoes, sorted by size. I can make out an imprint of a small figure pressing against the tent wall inside. It is quiet. I slipped by, just as quietly.

I was in the backyards of Crestwood now. There’s a broken fence and the cover of a bamboo grove to make it into the neighborhood. I emerged under a sign, “All Phones Armed with Mobile Surveillance,” and I appreciated the frankness. I kept a straight line. I cut corners, crossed over stoops, hopped a peace sign, drifted diagonally down long avenues. Spring Street, pointing east-southeast along the line with its turreted houses, felt like a march in a parade.

I had looked forward to the golf course. Here the straightline was to cross open fields made by mowers and exorbitant greens fees. I had hoped to evade soaring dimpled balls and hollers of outrage by the serious men repeatedly walking after them and whacking them with sticks. This segment was supposed to be the easiest and most in line with the Situationist creed. But a black iron fence rings the Old Soldier’s Home golf course. I stopped at the metal bars. They alternate in spirals that rise from the top like black horns of satyrs, which makes them sharp but also totally climbeable, like handles of ice picks, but the sign was imposing: US Government Property / No Trespassing — a shitty haiku, but a direct threat. It was also the Old Soldier’s Home and without golfers it felt like a shrine. I looked at the no trespassing sign. I looked at the satyr’s horns above me. A man screamed behind me.

He was running barefoot. He screamed for "Missus." He chased a pointy dachshund running for pure, breakout joy. The dog zagged, changed course, stopped cars, cut into yards and uprooted peace signs, and its exasperated, barefoot owner screamed in barking staccato, “Missus! Missus!” I set off immediately and ran along, too. The derailment from the straight line was complete; man and dog and I were in full flight down Pershing Drive. I sprinted left to outflank the dachshund. The dog saw my trick and bobbed down below a Ford Focus. We circled him until we had him square. It took some maneuvering to coax him to the edges, but the dog slid out by the clutch of its owner. Andre is the man’s name, and he repeated

Damn dog

as he pet its brow. We saluted each other with a nod. I said I had been going that way anyway.

Now it was a matter of picking up a straight line along Irving Street, spiking through the clover interchange of North Capital Street, humping through the woods of the Rosary Garden and drawing a few bloody stripes across my ankles. Just over Harewood, and through a stretch of woods and a hoppable fence, and onto the steps of the Basilica of the Immaculate Conception. I placed my shoes on the stone and rolled up my cuffs. I plucked a couple thorns from the raised red lines on my legs. I let my feet dry slowly in the cold sun.

My route was recorded. After the derailment and chase down the fence line, I had drawn across the northern half of the city a V.

~I.Re

pre-situ / in the margins, nov 21

man in box

I'VE SEEN THEM IN CRESTWOOD and Capitol Hill. They look into their hands at the front doors of their homes. Sometimes it’s the glow of their phones, but sometimes it’s their keys, and a few take too long to identify the shape they’re looking for. Something keeps them from going in.

Ninety years ago someone in a blank old house stubbed their toe on a box and found one of the most important metaphysical poets of an earlier century. The name below the verses is Edward Taylor, and before the discovery he was just dust to dust. He was a Puritan, and consequently he would have been in permanent dread over burning in certainty, and forever, which is main-dish dogma to the Puritan. His verse was religious. But the energy of his lines hummed underneath with a different sort of doubt: What if this were it? “My soul,” he wrote, “a product of breath divine... to illuminate a lump of slime.” In another he startled himself with the admission, “I’m but a Flesh and Blood bag.”

How many of these I see walking down Shepherd Street or East Capitol, pausing at their doors, stand as a sum total of salt and acids folded in a four-limbed bag? How many of them stop at only biology as the explanation for existence, a mechanical operation of limbs and jaws predetermined by the input of their optical nerves? Their headaches and hunger, their tired eyes and achy quads, their sinuses and scratchy throats: are these the only telltale symptoms of being alive? They know that this condition — the profound mystery of being alive — is quickly abates by the comforts installed and meticulously upgraded in the rooms just on the inside of that door, which is why, once they find the shape they're looking for, they quickly jam the metal into the door, twist the blade, and disappear into the theater of their homes.

Edward Taylor had been so startled at his own words, “I’m but a Flesh and Blood bag,” that he set himself to building cataracts of verse to overwhelm this line, to wash it out, to prove to himself that he wasn’t just a bag of human material. He risked blasphemy for the high style of his composition — and for the energy of his self-inquisition — to such a level that he asked his family to destroy his work upon his death lest it be damnably discovered. And then it was found in a box.

Taylor had been so alarmed at the physical riddle of being alive that he produced a box that could be found. While down the streets of Crestwood and Capitol Hill, you can hear electricity power meters spinning like runaway clocks with numberless faces, washing the dread away.

I’ve not seen anyone find their key, open the door, and then walk right back out. I’ve not seen anyone grab someone inside by the hand, and lead her to the illumined steps of Malcolm X Park.

Tomorrow, though, just in case, there will be cairns that will mark the way.

cairns

FROM THE BOG beneath the P Street Bridge, the last rocks were levered out of a kiss of mud. Slabs and bludgeons, sharp triangles and arrowheads. These were stacked onto a handcart, a black chimney of stone on a pair of wheels that will have to be hauled back up to the road. It’s winter dark, and the people beneath the bridge have not yet shown themselves.

This sort of dark takes time to survey. Graffiti on the back wall appears like a rune in infrared. There are overpasses and bridges all the way up the water: The parkway hangs over the creek’s edge and then bends over to the other side, and high above there’s the soaring backflip of Dumbarton Bridge. In scale, seen from the bone-wash bog, this is grander than the Seine and its jeweler’s tray of bridges because it’s not a Parisian advertisement, it’s here and now. Climb low enough and even overpasses soar. Arches and walls intersect like fingers in bat wings, and sticks in the water sail toward starbursts of lamplight. All this, for a single detour off the bridge, a descent into a latticework of limbs, a slide down an angle of leaves and a few hand-hooks on branches to the bottom. I was pulling rocks out of the creek as big as serving plates.

I heard the two men before I saw them. I thought a car had stopped in the middle of the span because I could hear its stereo, but it was just a small speaker twenty feet away. Two men in large buff coats sat on the bank and bobbed their hoods to a whistle and beat. Out of the gloom, distant and tinny, it’s the most alluring, unidentifiable instrumental I will ever hear. The underground scene in this city is alive yet, it’s just back underground. It’s left careful, repeatable venues and thrives in protest incantation, through small speakers bouncing off pavilions of bridges at night.

The first cairn was built in front of the dog-tooth tower of the Church of Pilgrims, the first church in the city to wear a rainbow flag and then a BLM banner. There is no one here — the only eyes watching gleam out of a statue of a Ukrainian poet whose memorial wreaths have all tipped over in the wind.

The cairn is an old structure, the oldest. It’s a burial marker, a tomb cap, a pile of rubble set in conspicuous geometry, a configuration set face to face by careful human hands. It’s a landmark, too, the version we know better, marking a stretch or the beginning of a path. The cairn stands in memoriam or in promise, but mostly it’s the mark of wherever you are, you are there.

These are placed up Florida Avenue, each with a small arrow of rocks pointing to the next. A man and woman I saw sitting in awkward repose at the Emissary Cafe, where I stopped to wash the giardia out of a little gash on my hand, will now have cairns to follow on their first date. They will have to move past the suffocating regret of the things they should have remembered to say, or should not have said, and instead find new curiosities that lie in the contours of every place they walk tonight.

Past the Quakers House and the strip club and Universal Liquors, the cairn to cross Connecticut Avenue was built at the foot of a Walgreen’s security guard. I told him, of course, about the Feast, an explanation that’s become increasingly a one-act play, and we agreed that the cairn will be removed once the Situation ends.

There’s a cairn in Brittany that’s seven thousand years old.

There’s now another in front of Lucky Buns, a quarter mile up the avenue.

The next one has to mark a detour. The entrance to Malcolm X Park is fenced off. The entire bottom section is wired in; the falls that step out of the thirteen basins to the pool at the bottom are held in the pitch of an extended renovation. Dante stands aghast. The strychnine eyes of Serenity, a carved woman slumped back in a chair, will never adjust to the dark. She’s remained too long in an allegory that keeps the TV on. Her nose is broken off. Her left foot erodes on a broken sword. She is finished, bloated, occupied and sated: irrecoverably serene.

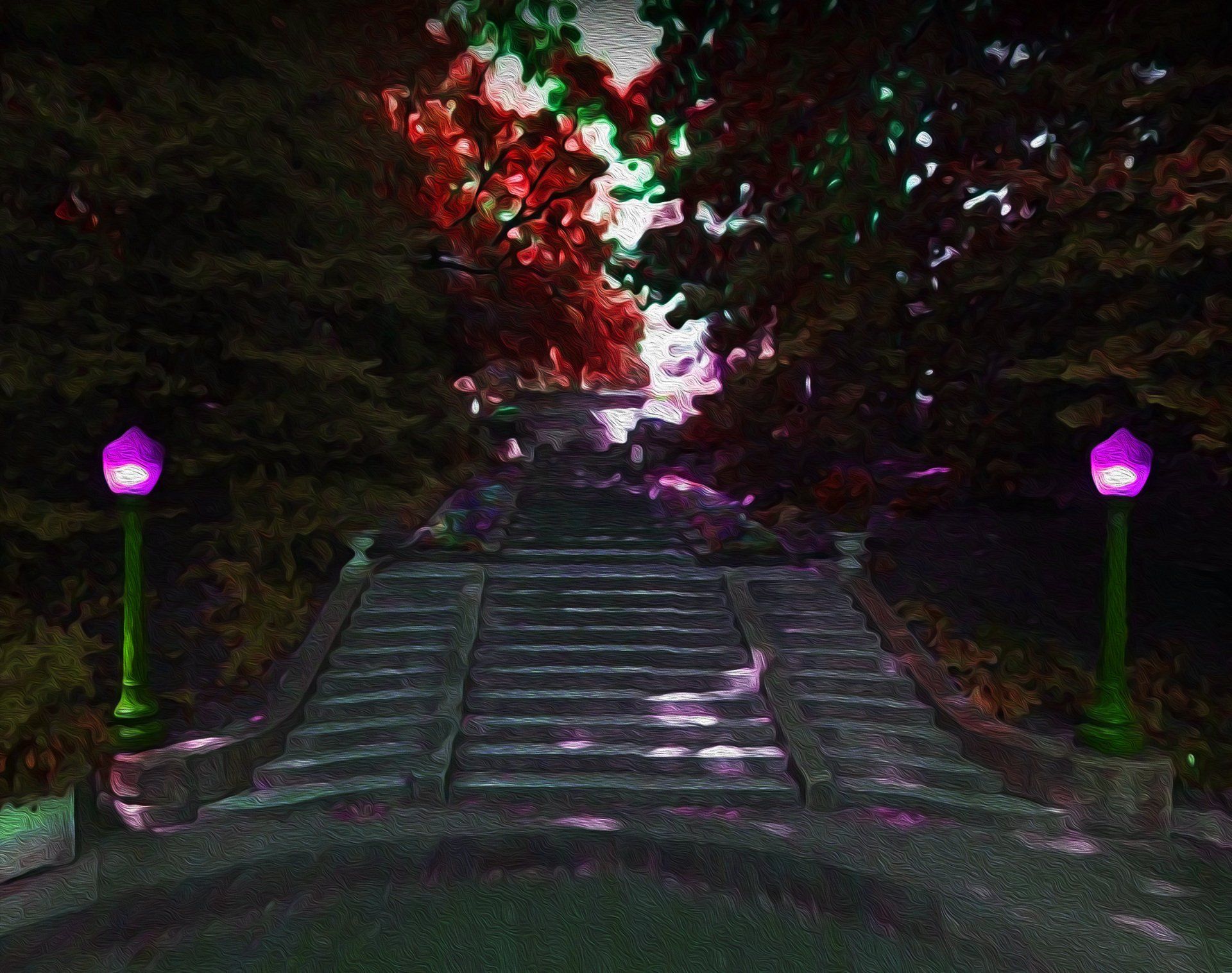

The cairn points up the steep hill of 16th Street. Halfway there is an arched passageway minus the portcullis. Its steps lead into a forbidding darkness: No One Dares Enter Here… but the cairn now built on the first step is oversized and perfectly clear:

Enter Here. It’s a stairway into blind faith that there is no one is inside, no one sleeps on the hard landing, no body lies limp on a step, no one will be crushed by a short stack of river rock humping up stairs. This gate enters a crypt risen from its entrance, a passageway into a hillside monastery where fallen monks stow their virgins in niches in the wall. But round the corner, the steps are perfectly empty. The dull light of the upper entrance witnesses only a man pulling a handcart full of rocks.

The plateau of Malcolm X Park is ringed by a pale lamp glow. Vacant benches line the periphery. In only one is there a body slumped over like Serenity. The wheels of the handcart roll quietly over the aggregate toward the top edge of the park.

The absence of anyone is surreal. The canvases of the drum circle have flaked off in an apocalypse no one knew had come and gone. On the southern edge of the park’s plateau, above an ocean of darkness, I built two cairns on the high railing. There were enough rocks to build two, and I wanted to see two. All cairns in the city now lead to these.

I sat on the pedestal of Joan of Arc, but she seemed unimpressed. I was, too. The city was empty, and nothing above the spans of its bridges had made a single surprise. For the unnatural act of depositing organized rubble along a major avenue, everything went too smoothly. I looked down into the chasm of the bottom half of the park. There was a single glint of light but nothing else. It was a vacuum to fill. There are steps on the side and no fences here. I walked down as if into the sea, leg after leg into the dark — a light makes a person vulnerable. I wasn’t too far in before I hit a rubble of aggregate. The pieces were large and flat, and perfect for bases. There was no one around.

Build the cairns

higher.

I stood on the railing above an ocean of darkness and built them higher. Satyr’s horns. A peace sign. A giant flying V. Antennae for some lost Signal. I don’t know what they are or what they mean. They are symbols without a referent. Stabs in the dark. Symbolists Eudora Welty and Melville famously denied their symbolism — in their stories there was just a man coincidentally named Cash and a white whale. The world can contain no more new symbols anyway; it has no use for them. There will always be new logos, but no more semantic totems or cairns. All we can do is to make them grand. Make them grand like obscure poets make their verses grand, as exhibits and proofs against their creeping suspicion that maybe they are just a bag of flesh and blood, a lump of slime out of a kiss of mud. These two cairns on the top of the city are as grand as the spires of Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia because they are here and now. Who can say what they are or what they mean or whose blood they fiber, but they’re built now. They are grand. And they are equal.

An ambulance moves slowly up 15th with its lights on. Shots are fired. The serene city sleeps under a new ontology.

The music is below, under bridges tonight. November 22.

~I.Re

post-situ / under bridges, nov 24

mortals

"Among the Immortals, on the other hand, every act is the echo of others that preceded it in the past, with no visible beginning, and the faithful presage of others that will repeat it in the future,

ad vertiginem. There is nothing that is not as though lost between indefatigable mirrors. Nothing can occur but once, nothing is preciously

in peril of being lost. The elegiac, the somber, the ceremonial are not modes the Immortals hold in reverence… Outside the city, I saw a spring; impelled by habit, I tasted its clear water. As I scaled the steep bank beside it, a thorny tree scratched the back of my hand. The unaccustomed pain seemed exceedingly sharp. Incredulous, speechless, and in joy, I contemplated the precious formation of a slow drop of blood. I am once more mortal, I told myself over and over,

again I am like all other men. That night, I slept until daybreak.”

~Jorge Luis Borges,

The Immortal

(As discovered and sent to us this morning by Ray S.)

chinatown

I HAD A SPARE TOILET, so I was on my way to inspect for any availability in the Hirshhorn sculpture garden. What’s the blasphemy of placing a newly painted, bright yellow commode, a free-standing toilet in that collection of art? It’s an absurd question; all art in that garden owes its existence to that toilet, for once Marcel Duchamp submitted a urinal to the Grand Central Palace for an exhibition, all definitions crumbled and everything became art at the same time. So you can have your warped and bulbous geometry littering the grounds in their respective places. Depositing a toilet would be the most traditional tribute I could make. It would offend only the ignorant and the young, who should be offended as part of a better education. I would simply become the ghost of Duchamp, a concomitant spirit of that mystery visitor to Poe’s grave for 75 years, but instead of leaving roses and a bottle of cognac on an anniversary, I would install a toilet in the garden on an ordinary day, the greatest tribute I could offer: the demolition of all taste and sensibility. “I consider taste — bad or good — the greatest enemy of art,” said Duchamp, unaware that in the next century billions of people would be daily beholden to likes and dislikes, hearts and empty hearts, thumbs up and thumbs down, followers and faceless figures, all children at the big table telling us what they like or dislike and throwing peas at the dog. I had a toilet to give and a site to inspect, its approach and the number of security guards, the routes they take and the their sight lines, when I saw a man sprinting up 7th Street.

The decision I have to make is obvious.

A lesson of the Feast is that if you are in a place long enough, unscheduled, something wildly unusual happens. The variables are too great for something not to happen; primitive emotions spiking the hearts of everyday people are just too weird — unharnessed from politeness and programs, those breakout emotions are our only possible salvation. The machines of entertainment have exploited and mollified these for too long; eventually that primitivism will break the machines. Something is bound to happen.

The second lesson of the Feast is to be ready for it, any seismic flittering at all. You must be ready to run with it, or Serenity will claim the rest of your days.

So it was obvious. We’re running now. He was a big man, dressed in working clothes down to his sensible shoes, so he wasn’t a jogger. He ran in loping but long strides. I couldn’t make out why he held his left arm behind his back. He ran down the wide sidewalk, and I took to the street. I gained upon him. The street is always faster. In the city of the future, in the city we want, cars will be banished and there will be lanes for the speed people wish to travel, some designated for the slow, rose-smelling, curious and life-loving daily revolutionaries we need, and the rest for everyone who runs — for in the future we want, everyone will run. Watch a playground and kids sprint five feet to the next slide or to examine the thing another kid holds in her hand, a weirdly shaped rock or piece of colorful glass, something that demands immediate attention. In the city of our salvation, people won’t jog, they will run to each other, to see what they hold in their hands, or to keep up with their lovers on freely borrowed bikes.

There’s no apparent reason that this man should use one arm to swing for his loping gait and hold the other behind his back. I can’t make out if he’s holding something.

There’s another man running ahead of him in the distance. His long black curly hair bounces and whips like a man being chased. Now I know the plain clothes and the sensible shoes and why these two men running aren’t joggers. We round the block onto H Street. Chinatown. Chinatown at speed is a plate of red splotches. The man of bouncy, curly hair is distancing his pursuer.

We come to a stop. The man with his arm behind his back takes a few landing strides from his flight and looks at me. “You know him?”

“No, I was just finishing a jog. I was trying to catch up.”

He stares at me for a few interrogative seconds and turns to walk back to 7th Street with a small limp. He makes a phone call. I look around. I’ve never seen this part of Chinatown and so I walk to take it in. The lampposts raise little green hutches of plated glass on pleats of red spikes. The post in front of the synagogue bears vertical Chinese characters in black marker. In other languages graffiti always seems to promise a parcel of wisdom that might just explain everything. On the other side of 6th Street the curly haired man is running back this way. He’s young, and doesn’t look like he’s slowing at all. Why is he still running? At the bottom of the block, he turns down H, past Capitol Sushi and Chinatown Liquor.

I like to think the chase continues, but swapped. The boy in curly hair chases the one-arm man. Time keeps resetting and starting over, revolutions spin into revolutions and then into insurgencies that incite the atonement of new art, the dismantling of all working definitions and the annihilation of taste. They keep running after each other, swapping spots, and the whole city begins to rotate under their feet until we’re all dizzy. We forget which way is up, which way we were going; we lose ourselves, discover the little green hutches trickling out beads of wisdom in unknown languages, and find that’s where we were supposed to be all along. We hadn’t known we were looking, and that we were looking for something we didn’t know existed. All this time, we hadn’t known we wanted More, more than we had before we turned and started running.

~I.Re

voices in cabinets

THERE ARE CARD CATALOGS on the streets tonight, those old boxes that once held the keys to Babylon for over two centuries. Tonight they are pink, rough, thin and warped. The top drawers hang out like tongues, their acid tabs not stacks of machine cut cards but squares of blade-cut paper. The trays are stuffed with paper, catching wind or the ungloved fingers of tonight’s crowd migrating north to dinner.

Among them, they read:

WILL SOMEONE FALL MADLY FOR THE THING YOU DO IN THE COMING HOUR?

~

YOUR MATES ARE THIS CLOSE TO BECOMING TIRED OF YOU.

SPEAK NOW WITH URGENCY ABOUT THE ROMANCE OF CHANGE.

~

CONVERSATION BEGINS THE MOMENT YOU REALIZE THAT NO ONE AT THE TABLE — YOUR COLLEAGUES, MATES, AND ESPECIALLY YOUR LOVER — WANTS TO HEAR ABOUT YOUR WORKDAY. CONFESS YOUR HIGHEST SANCTITIES, YOUR GRAVEST DOUBTS, AND THE AWE AND HORROR AT BEING ALIVE.

~

IT IS NOT SELF-BETRAYAL IF YOU CHANGE ALL YOUR VALUES, TASTES AND SENSIBILITIES BECAUSE YOU HAVE BECOME BORED OF YOURSELF.

~

THE ONLY IRONY IS THAT YOU PARTICIPATE IN IT.

~

TONIGHT WILL YOU TALK ABOUT WHAT YOU’VE WATCHED,

OR WHAT YOU’VE DONE?

~

LIVING IS A SECULAR RELIGION.

ENTERTAINMENT IS ITS MURDER.

~

THE IDEA OF BEING TRUE TO YOURSELF IS A TRICK. WHAT YOU BELIEVE ARE YOUR INSTINCTS WERE GIVEN TO YOU.

~

ANNIHILATE CONSISTENCY — IT’S THE ONLY WAY TO RECOVER THE PERSON YOU ONCE WANTED TO BECOME.

~

THE GHOST OF YOUR FUTURE UNDERSTANDS THAT YOUR SANITY NOW DEPENDS ON MAKING EVERY DAY ABSURD.

~

IF YOU THINK LIFE IS A PRACTICAL JOKE, GET REVENGE WITH YOUR OWN METICULOUS ABSURDITIES.

~

HOW OFTEN DO YOU CATCH YOURSELF DOING NOTHING THAT MATTERS IN THE END?

~

THE REASON YOUR PHONE HAS A FLASHLIGHT IS SO THAT YOU CAN EXPLORE THE PARKS AT NIGHT.

~

STAND ON TOP OF THE BED AND READ TO HER AS IF EACH PASSAGE WAS A PROCLAMATION.

~

TONIGHT YOU CAN SAY I DON’T WANT TO TALK ABOUT THAT ANYMORE: SWITCH THE SUBJECT TO THE SCALE OF THE UNIVERSE, THE PROOF OF ENCLOSED WORLDS IN GLASSES OF WATER FLECKED WITH POLLEN, AND THE ABSURD CONTRADICTIONS OF ORIGINAL SIN.

~

IN THE MIDDLE OF DINNER, EXCUSE YOURSELF TO THE BATHROOM.

WALK OUT TO THE STREET. SEND A MESSAGE.

TELL HIM TO MEET YOU AT THE GATE OF THE OAK HILL CEMETERY.

~

… TELL HIM TO MEET YOU DEAD CENTER OF THE DUMBARTON BRIDGE.

~

… TELL HER TO MEET YOU AT THE SHROUDED FIGURE OF MARIAN ADAMS, AND THAT SHE WILL BE OUR LIVING ANTITHESIS, FINALLY UNVEILED.

~

… TELL HER TO MEET YOU AT THE TOP OF THE SPANISH STEPS ON 22ND STREET. WHEN YOU FIND HER, APPROACH HER SLOWLY FROM THE BOTTOM STEP, WITH TREPIDATION AND AWE AT THE UNREPEATABLE NATURE OF THE MOMENT.

///

Think of it, on the top step she turns to face the downward slope of 22nd Street and the glow of three embassies. She wears her red jacket. Her scarf disappears and curls around her on a slip of wind. The two security lamps on the street above send out flares of emulsive light — outlining her figure in two silhouettes. At her feet, the two shadows split into forward-swept wings, spread like black drapery across the stairs. It is a vision beyond spectacle, a circumstance instigated by uncommon volition, one that arrests time and narration because the words will have to come much later. They come now and here in this page.

No mass audience can ever attest to a memory converted by a single set of eyes.

~Feast

Post-situ / convergence, Nov 29

this night

A BOTANIST, not a chemist

What Brown noticed was that tiny grains of pollen suspended in water remained indefinitely in motion no matter how long he gave them to settle. The cause of this perpetual motion, the actions of invisible molecules…

~Bryson

To see a World in a Grain of Sand… [to] Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand / And Eternity in an hour.

~Blake

In all love there resides an outlaw principle, an irrepressible sense of delinquency, contempt for prohibitions and a taste for havoc.

~Aragon

Beauty will be convulsive or will not be at all.

~Breton

We have sought permanent novelty:

The test of a gas station flower, writing people back into history, revivifying ghosts on the mall and chanting primal screams for piano insurrections; placing all-encompassing Black Squares into the wind, stepping off bridges and falling from scaffolds of high principle to dance, to enact quarter-mile sabotages and incite resurrections from typewriters, single leaf-cuttings, corsets and basslines; soon there will be cliffs of ivy, open-air opera houses and psychedelic buses — and moats of fire, reckonings in the blue haze of small clubs and ladders to the moon... already barriers have been turned into benches, lines drawn directly over hills and fences to the sun-steps of the Basilica; baroque verses found in boxes, music from bridges, and cairns from bogs; there are now two equal towers of monumental aggregate and stone at the top of the city; and from a chase in Chinatown, between little green hutches of plated glass, and down runes of graffiti, we find that the only thing missing is More.

Meet me at the top of the Spanish Steps tonight. They are at the breakage of 22nd Street.

~I.Re

the equation of everything

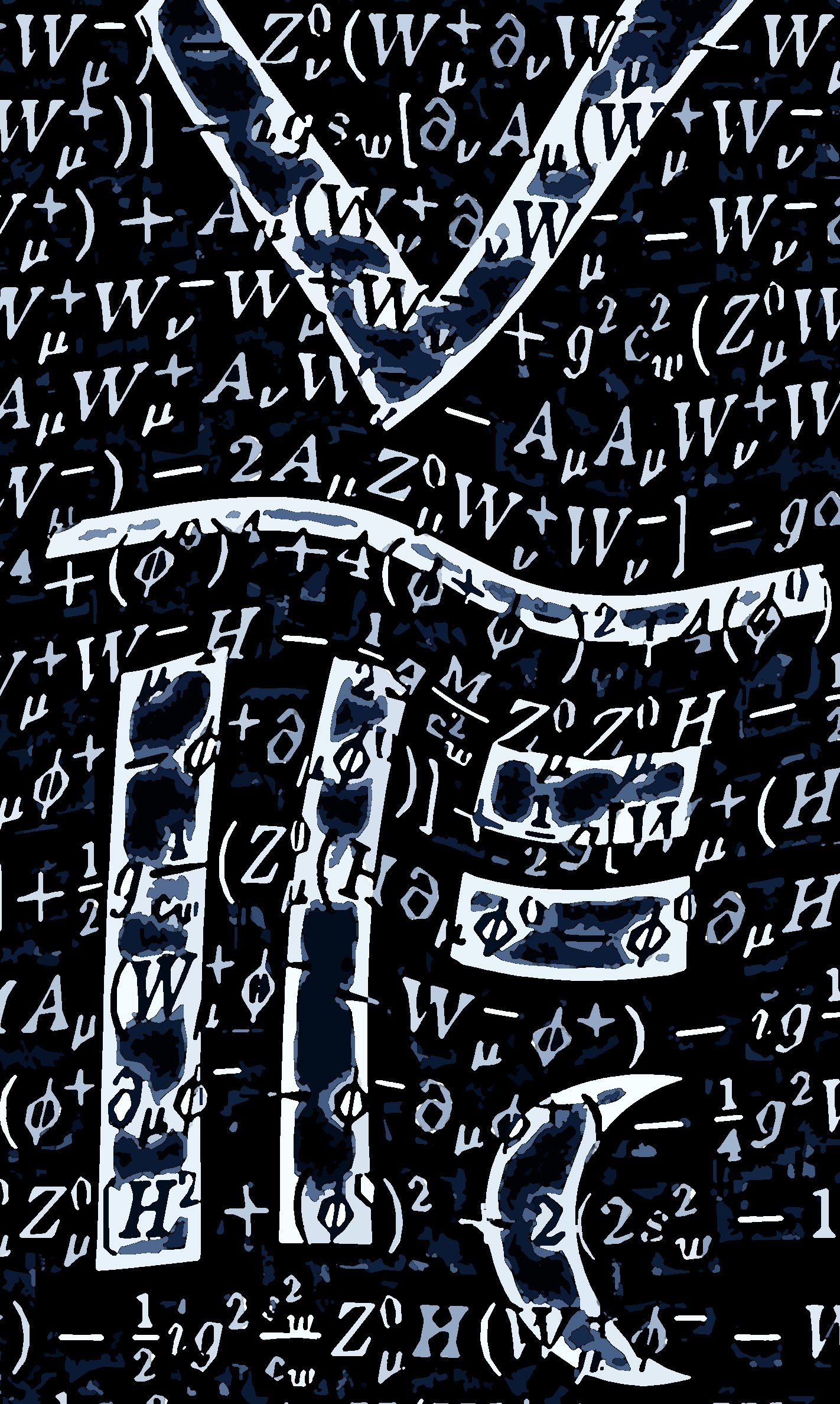

THE BAG SHE HELD TIGHT to her chest can only contain the full and only download of a soul. Why else? Why else would she hold her bag that way, so near? She passed by me at least four times at the steps of a masonic temple. She stopped and stared at the large format paper spread before me like a busted up mosaic.

Scrawled out on sketch paper in black marker is an excision of the Standard Model, expressed cleanly, I’ve read, in the Lagrangian form. It’s a so-called Equation of Everything: symbols and statements, rules and inferences, axioms and syllogisms that, taken together, cleanly express the existence and movement of everything —

Everything, a ToE, a Theory of Everything, expressed in a mathematical framework, Everything in clean logical notation, things and movements, nouns and verbs, a totality of expression superior to all other languages because it strips out everything else, all modifiers and adjectives, all extraneous nonsense, all intention, want and reflection, the raised print on tea cups or the questions following an assassination.