vol 3 / now there are thrones

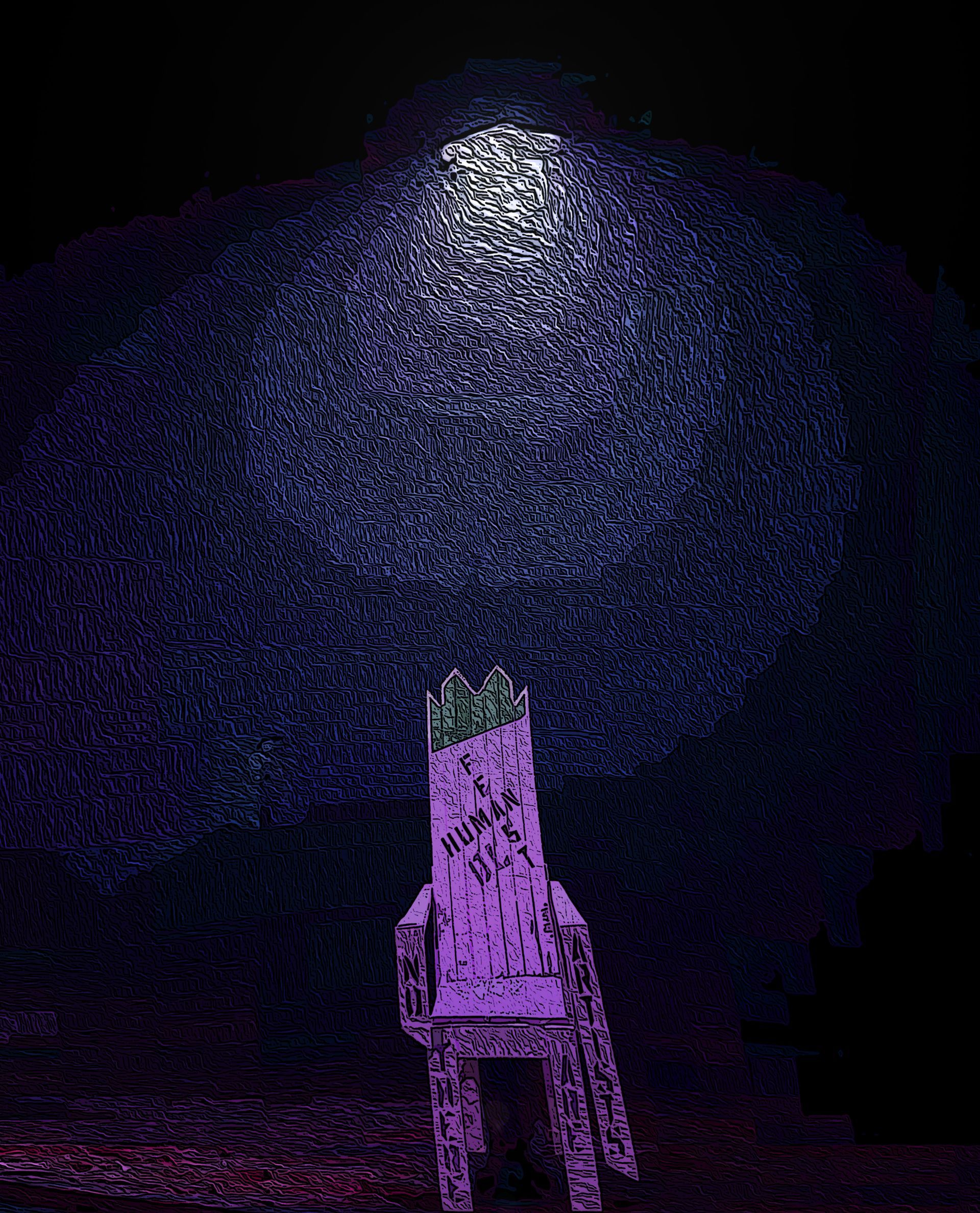

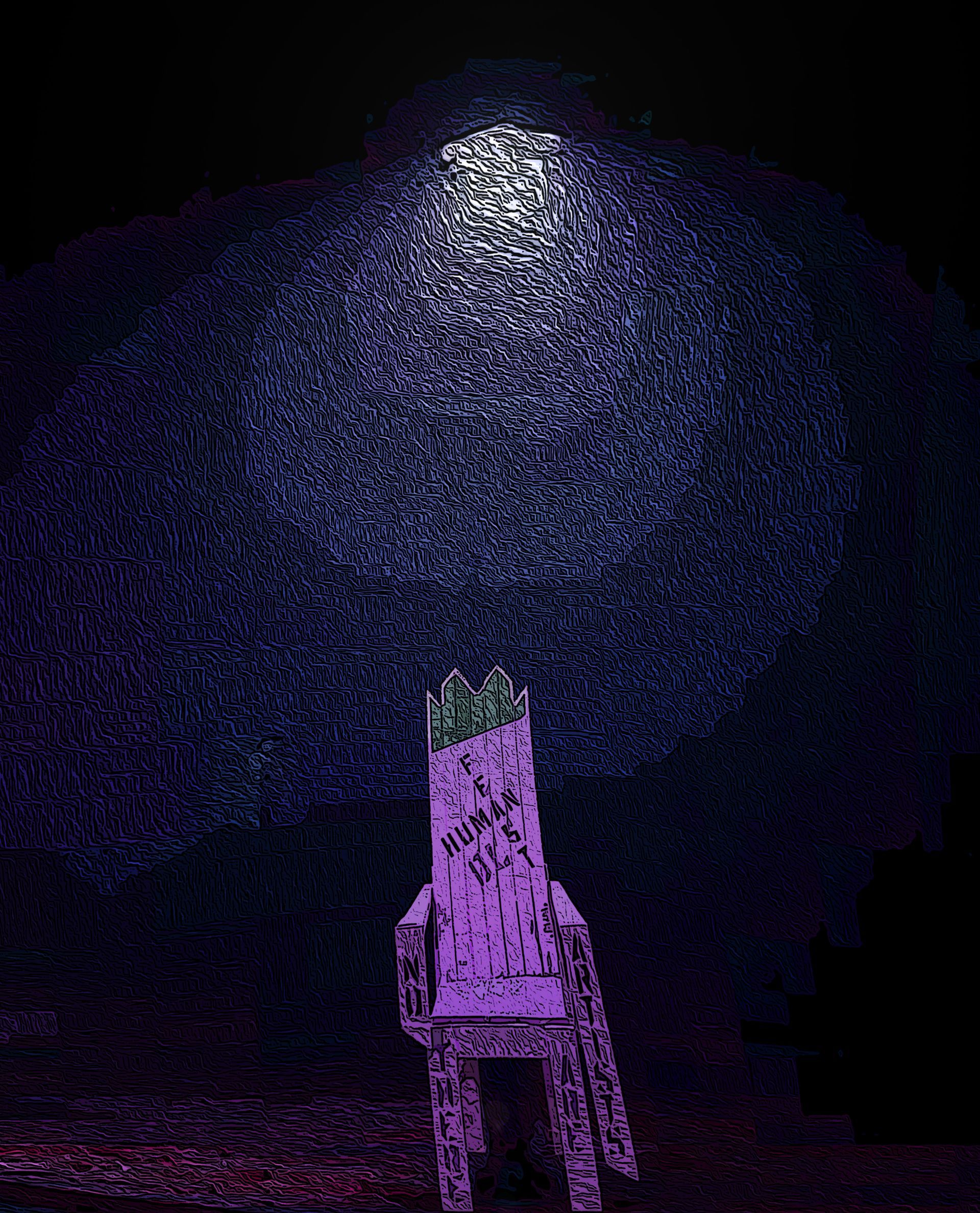

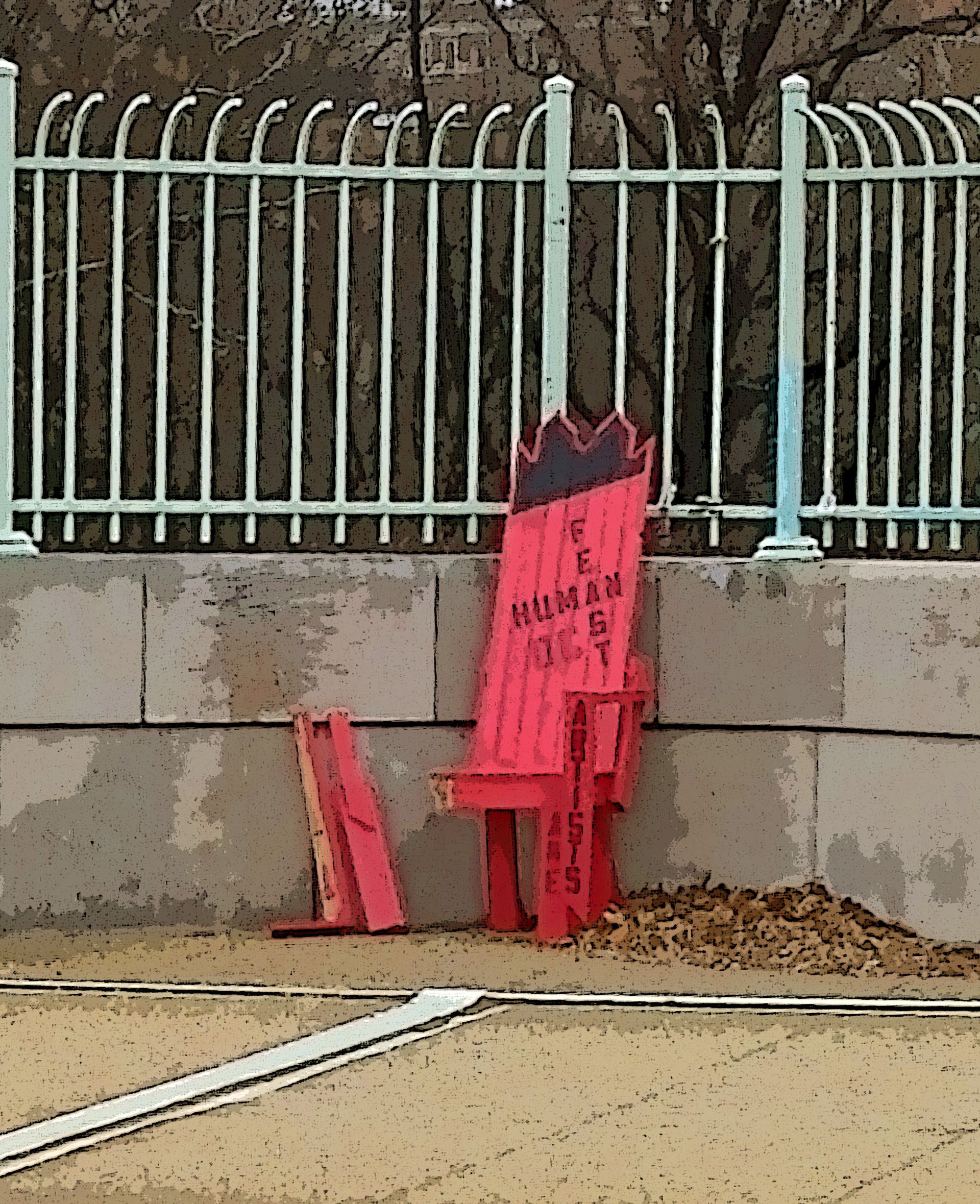

THE BENCHES OF LAST SPRING have split, spiked and multiplied. There are thrones now. They are the seals of an imagined future, or emblems of the past, a sovereignty repeated and duplicated in retrograde symmetry. They are either the promises of insularity — we sit in lonely dominion — or of coronation — a Human Next.

This summer we tried less to proselytize than to raise the points of the Human Feast — this odd society, collective, cult or troupe — this group that shapeshifts, like all societies do, to bear messages, rumblings and warnings through the nodes of its members, its warm, discrete, throttling bodies trying to communicate something big and ambiguous and earth-shattering.

We tried in the places we had decamped to this summer, from bare-backed trains of India to wool-socked huts along the Continental Divide, to reiterate the points of last spring: that There Are No Strangers, that we are rhythmically by art, and algorithmically by machines, being smashed and mishmashed into a single consciousness; that art and music have by its routines and subroutines — by constant, iterative taste-testing, by data-driven likes and dislikes — prepped us for Turing-test mimicry and subjugation; that language itself is the original integrative software, and the original *killer* app. There are no strangers because we all think the same; even our differences are recognized and repeated by consent. The only breakthroughs we can have at this point must be unscripted, and rough.

The Human Feast benches of May told us everything by the people we found sitting there, strangers and no strangers sharing the same space.

Now there are thrones. The points of a crown. Grand little fiefdoms. They dot the city. The members of the Feast are clearly back, and so are we.

We hit play.

witnesses //

nov 10 / we count twenty

WE'VE COUNTED TWENTY so far. Titus had spotted three yesterday morning, spike-horns of painted wood; Helmut spotted four in a square around his apartment; Sisfit counted two up near her place north of Malcolm X; I’ve seen three on the campuses of American and GW. We've been adding to the catalogue.

Little fiefdoms sprung of blood. Nubs or bleeding teeth. I could hear these — they came out of a session: Why thrones? I walked a stretch of Rhode Island Ave through Shaw. There are two thrones here, empty. The most play of any has to be the one south of Dupont. It’s become a high prize of portraiture. I’ve seen walkers filling in as their own subjects, snapshots of afternoon keepsakes, exhibits A to Z, reviewed and curated for that day’s proof of a day well scored, tallied and kept in the books, less serialized than slapdash illustrated. I’ve walked by and offered to take a picture; one sat on the lap of the other and the two of them flexed out some over-the-top smiles. They were beaming. Their teeth needed no sunset, they were the hour before the time. They thumb through the pictures. Their faces become dead serious. Pinching the screen for close inspection before agreeing, yes, that’s the one. Their ideal projections are sent out and everyone on their list can cross off their names on the daily triage of everyone they know. This is public living. Accounted for. Two smiles, completed.

These are not fiefdoms. The thrones can be a fine prop, but they are more: council chairs, tops of turrets and mountainside lookouts. The thrones for kingdoms are those that look out. (Earlier this morning a girl named Rayna had asked me what narcissistic meant. She asked in a whisper because she thought she knew but wasn’t sure. I showed her a painting of a flaxen headed prince staring into a head-shaped puddle, Narcissus.)

The throne in Shaw was occupied. A man in a blurry, camel-colored jacket sat slumped to the side, nudging his lips past his nose. He took no pictures. He accepted no self-delusional packets of frozen time. He looked out, instead. He surveyed his little dominion. In him there were Whitman jets of blood. He held court.

These are the people the thrones count, the last types recorded on Earth before the thrones are swapped out for clean, hot air.

nov 11 / TYPOLOGIES

WHO WILL WE FIND? This was a pleasant anticipation last spring. The benches were shared: There Are No Strangers was stenciled onto the slats. Beyond props for portraits or whimsy, who will sit in these? The thrones seat one. How do we share space to vacuum in a conversation when there’s no proximate air to share? Pretty quickly we knew we’d have to move a few thrones next to others. Sovereignty, a kingdom, will have to wait. We want to talk.

It was fairly immediate that sitting first in the thrones created better invitations. We risked the splinters, and people came to sit. Now they’re stadium seats, balcony chairs to watch the flotsam wash by.

I tend to trust the ones who sit and bounce a leg on the knee of the other. Let’s muse: this is the posture of thinking men and women. The thrones start the session. “We don’t know where they’re from.” “They’re oddly comfortable — for small durations.” “They do feel real.” “The Human Feast, it’s some group.” “I don’t know, honestly.”

I wanted to keep a list of the people who sit in these. Helmet and I developed some scratch-brained hypothesis that the twenty thrones will seat, and put on display, typologies of people. Scolds and leeches. Middle-men. Sacrificial mothers. But we couldn’t avoid the old generalities. They had names last spring, each person we talked to — if you talk long enough and ask the right questions, people will defy the old typologies. But there’s something about thrones, said Helmut, that removes them from personhood, that distills and reifies them into representations, that makes clear the boundaries of the little, dwindling, partitioned fiefdoms they survey.

It’s a consideration. At no other time in history have we been so cognizant of the eight billion people around us. Never have we been so attentive to war on far strips of broken land. Never have we known with such intimacy the names and daily inanities of people who know little of us, except that we’re watching. Never have we read the thoughts of some emerging zeitgeist with such repeating alarm. Never have we been so diligently trained to bear the same reactions, responses and impulses. The Human Feast is right in that regard. We’ve become a mash, a slimy ooze, a material of sustenance for large scale operations that must feast on us for empire. That must compartmentalize, tribalize and trivialize; that must commodify, pit and bracket. It’s not alarming, not anymore, when they admit to the point of boasting that that's their business plan.

So maybe there are twenty different types of people left to represent eight billion. The militant. The fixer. The siphon. We came up with these names but they all begin to sound synonymous. Besides, said Titus last night, tapping his fingers on the planks that drip like eaves from the armrests, we have met no artists this week.

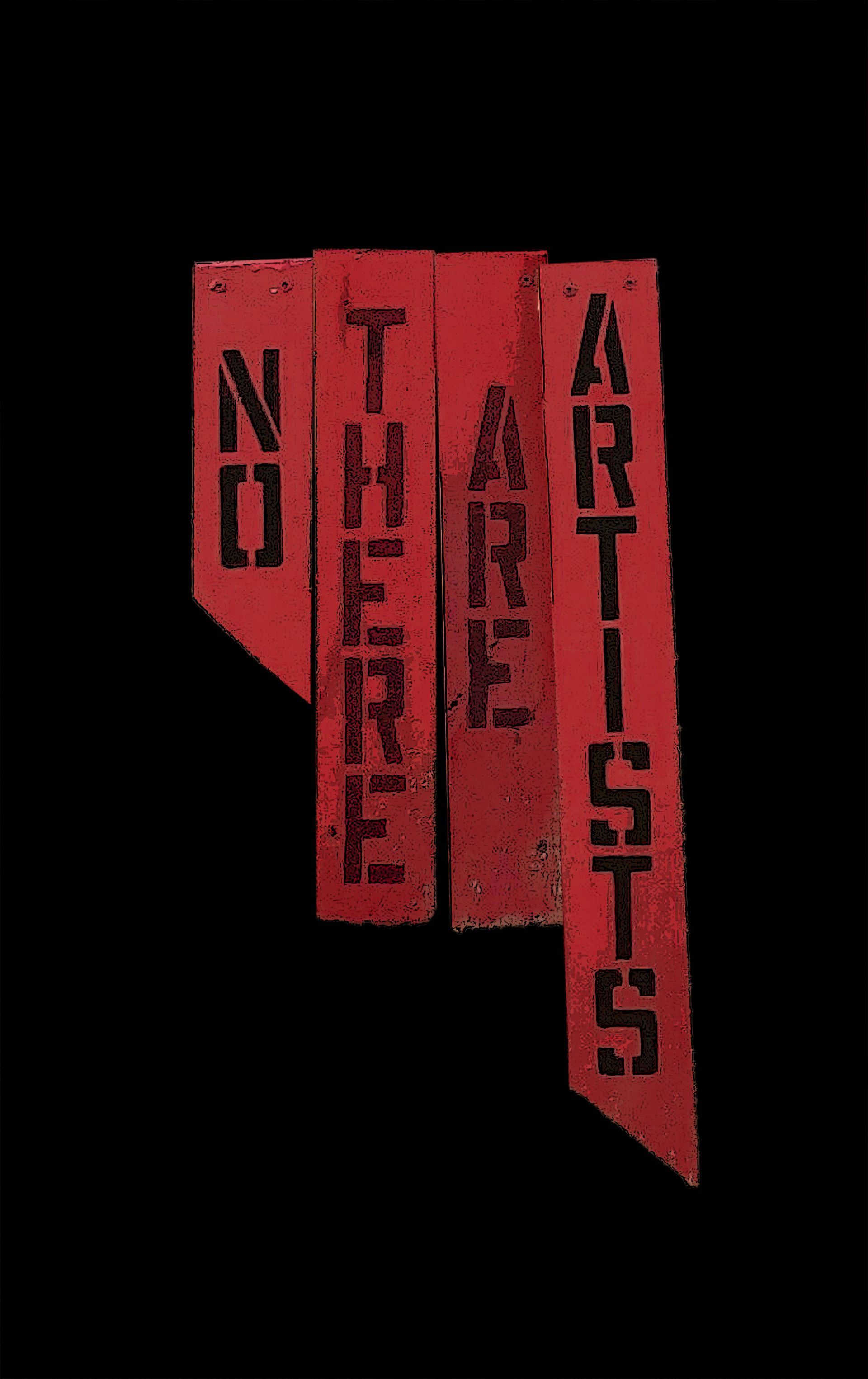

“This is their argument,” he said. “That There Are No Artists.”

nov 12 / fire in the sky

We moved a throne next to another on 16th Street. We’re taking liberties with these as we did with the benches last spring. That the thrones were built and placed by others presents us with no dilemma; we suppose that the Human Feast collective, having first commandeered our name, have co-opted our aesthetic, too. Our original manifesto has demanded a sense of play from the beginning.

We took up a couple thrones and placed them side by side, a happenstance alliance. We ate jumbo slices of pizza. We returned to the site.

She had been there first, and I set up next to her. We faced the street, clusters of condos before us in the office alpenglow, embers cooling in the big November drop. She sat high: such an erect posture, her back straight against the painted slats, arms covering the rests sphinxlike. She wore a white sweater that curled like foam around her long neck. Black stockinged legs, one bouncing on the other, 120 beats per minute, the tempo of our hypnosis on a global scale. There were no words tonight. There was too much to observe, too much to lord over. We were stills. We must have looked like those old portraits of residual monarchs in their little, ipso facto principalities at the dawn of colonial subjugation. We were still, quiet and dignified, lords over disappearing terrain.

I surveyed. I’ve known majesty, walking a city boulevard when the city sleeps, 3 a.m., with another, the last couple on the planet still aware of the flamboyance of the present, out and about on the city instead of smothered in panicky dreams in bed, where Monday to-do lists anthropomorphize into tiny hands grabbing at legs between the sheets.

I’ve known the majesty of walking with someone in the sleeping city, down along the Reflecting Pool where street lamps cozy up the fog with swirling light.

Above us, this night, from the position of our thrones, a tiny flame spun in the air high above the top floor of the building across from us. There were more. They looked like papers on fire. Heated into propulsion, some lifting, some descending like spits of meteors. Plies of airy embers, leaves sprung out of camp fire, or sheets of toilet paper. Yes, it looks like Attica — prisoners setting strips or entire rolls of toilet paper on fire. Pyrotechnics of an invisible riot, fireworks before the inevitable backlash. Little flames in the sky. It seemed so strange.

Wait anywhere in the city long enough — outside, with eyes out, in complete disparagement of ritual or program — and there will be rewards. Stars spritzing over the Korean War memorial. A deer on the national mall, fully antlered. Tiny flames dialing in the sky. With so many pieces at play in the complexity of our daily machinery, there’s just so much that can go so beautifully wrong, so many gorgeous spectacles of near-catastrophe, so much that can be out of place at the right time.

I knew if anyone looked up at this little arsonist exhibit, cameras would come out to furnish testament of a thing happening. Proofs. Exhibits. Little screen-wide captures of consciousness, tiny verifiable experiences to share.

All I had to do was look to the throne next to me.

At some point, though, she had left, and the throne was bare. The sheets on fire doubled.

nov 13 / we'll handle the upkeep

In spring the Human Feast had installed two benches in Adams Morgan, upper and lower. This neighborhood has not flagged for decades; it does not disappoint. All of Dupont and the new coliseums of Southeast may have risen from poppy fields to Emerald Cities to glass-coffin sterility. The corridors of H and U continue to contort out of fumes and haze. Nightclubs photosynthesize into condo storefronts. But AdMo has kept its ethos, defiant of banks and stratification, a mash of mixed-use, storied haunts and rooftops. Today the only thing missing is an orange cat.

A throne at the top of 18th, a throne at the bottom, we moved them both to the middle. We’re still suspicious of the thrones as decals of isolated sovereignty, or as the last outposts of self-control. We want them to be social, benches or loveseats on the concrete veranda of a city. So we moved them and sat outside of Heaven and Hell and watched the world go by. We hadn’t noticed any cat.

“It’s a tabby,” the man said, adding that it was his girlfriend’s cat. “Kepler” is its name. Had we seen it? We looked around, and then down and around our seats, always a performative gesture to sympathize with anyone who’s lost something. No, we had not seen any cat. Kepler’s man stood there in surrender, in pajama pants, a black t-shirt, a sleeve of samurai tattoos. Helpless and hopeless. Helmut said we needed that mythical facility of spies and assassins to recall every detail of a scene, down to the silver cigarette case behind the bar. There’s just so much we miss. Kepler’s man growled, “this thing is invisible.” He laughed despite himself and the growing threat of his girlfriend.

We spent the hour swiveling our necks into early arthritic wear. The man left and we thought it responsible to keep up the performance, although I really did want to spot that cat. It was sunset and the thing would be a blur. It wasn’t more than five minutes before the man returned, resigned he would never find that cat until it wanted to be found. Helmut ran across the street and brought out a Sunkist for the man, who laughed at the gesture.

We agreed that we spend our lives moving things around. It’s a conservation of matter — nothing escapes; we just move things around, shoe bins, jars, picture frames, dishes used and washed and stowed in triangular trade. Cars are moved between spots in which to put them. It’s a conservation of matter, but not of energy — that we spend toward the closing of our days.

I took a walk because I imagined I'd see the cat. Don’t you think it’d appear if you just put your mind to it? When I returned Kepler’s man had taken up my throne and his Sunkist sat on the armrest unopened. I sat on the ground: There Are No Strangers.

It occurred to us that surveillance cameras of the future will record the future. They will record what happens next, before it happens. It’s just a matter of processing speed to account for the rate and velocity of every object and person, simply a matter of evaluating the trajectories of highly predictable large-units in an increasingly deterministic, known and tabulated universe. What the cameras won’t capture, replied Helmut, “are fingers and cats. They’ll be blurs in the background, low-res, inessential.” Kepler’s man had read about the difficulty of rendering fingers, too, the inability of machines to produce portraits with realistic hands, sharply, with the correct number of digits. Right now it’s a check against fraud, a signature error, the revealing “tell” of machine-made imagery. An oversight that will, like all others, be corrected by rapid iteration. “But that’s just it,” Helmut said, “those pieces of machine-generated art: you’ve seen the trippy futuristic renaissance digital paintings—” Those scenes with ballroom women in front of a colossal moon? “Yes, those. The hands are all strange and blurry because the details are besides the point. We — the human — we will keep up the maintenance; that’s our job, handling day-to-day things and all the perishables, all the upkeep” — like the railroad worker we saw last spring, a self-repairing, dispensable, replaceable human piece of equipment that excels in moving things around in fluid settings — “yes, and the machines will handle the big-picture visionary things, like music and art” — as well as instructions to nuclear disarmament and carbon detoxification.

Kepler’s man noted the time. He said his girlfriend is going to be right pissed, but it wouldn’t be the first time. That cat will come back, he said, right after he catches hell for losing it. It’s always this way. “And we’ll do it all over again next week.” It’s part of the upkeep. It's routine maintenance while something else emerges out of the haze, while we’re busy looking for lost things or moving found things around, all to carefully recommended playlists, between programs, while the cat, free and trapped, alive and dead, festers in a box.

nov 14 / Uberman

I dragged a throne back to the north end of Adams Morgan, in front of a plaza that bears tributes to the dead across its no-trespassers fence. The condos that will eventually stand here will make a killing.

A man paced in front of me. He drew circles in the air. He was a big fellow, dressed in a suit that he probably slept in, wrinkles smoothed from the weight of an unsympathetic world… no, that’s a cell phone he’s waving; a cab had passed him by, one of those red ones of the Yellow Cab Company, which does its best to invoke the color play of the Dadaists. The man, snubbed hard, turned around and saw behind him a man sitting on a throne. Now he really looked annoyed. He returned to his phone, and I could see the white lines of Uber splitting open a lid to a more palatable view of the city.

He had to wait, though. He looked back at me. “Is this some sort of protest?”

I said, “It is.” I had the backing of memorial photos and plastic flowers, but the response was reflexive. It is “some sort of protest,” as much as he is some sort of man.

I asked him if he had any opinions about the plaza. I remembered the timeline of deadly transgressions by Truist Bank and I told him the highlights. I told him about Miguel Gonzales, a name that has lodged in my memory since last year. The man was unimpressed. His phone scattered light across the ridges of his face. He held the screen open like an electric hymnal. It promised deliverance in 4 minutes in the vessel of a white Camry, license plate DCH-XXXXXXXxx. Just four minutes and he would be taken away from this blighted corner of town and into a bath, or glass, of suds.

He muttered, “We all build on the dead.” He didn’t look up when he said this, his eyes fixed on the black avatar of a car spinning across a simplified grid. It was hard to hear, and maybe he said, “We all live on the dead,” which is a more elegant paradox and a glaring fact of biology. Anyway, it was his zinger, and he washed his hands of it all, sudsed it up and swiped it away.

“There are more people alive on earth today,” I said, “than have ever lived.” I don’t know why I said this, or how it’s a retort at all. I’ve read that this astounding statistic is wildly off, but there it was, in the air between us. He scowled at the screen, and his face froze until the Camry (which was actually gray) swerved over to rescue him.

It’s not true that we outnumber the dead. Arthur C. Clarke wrote in 2001: A Space Odyssey that “Behind every man now alive stand 30 ghosts, for that is the ratio by which the dead outnumber the living.” Clarke estimated that there is just enough space in the sky “to give every member of the human species, back to the first ape-man, his own private, world-sized heaven — or hell.” Either way, it’s his own dominion.

That was 1968. Now the ratio is closer to 15. The real estate of our afterlife has been cut in half. Such is the rate. We’ve been partitioned, reduced, built upon.

I sat. I presided. I could hear horns and sirens competing across the city. These are the horns of drivers and the sirens to collect them. It’s an ecosystem. A feeding.

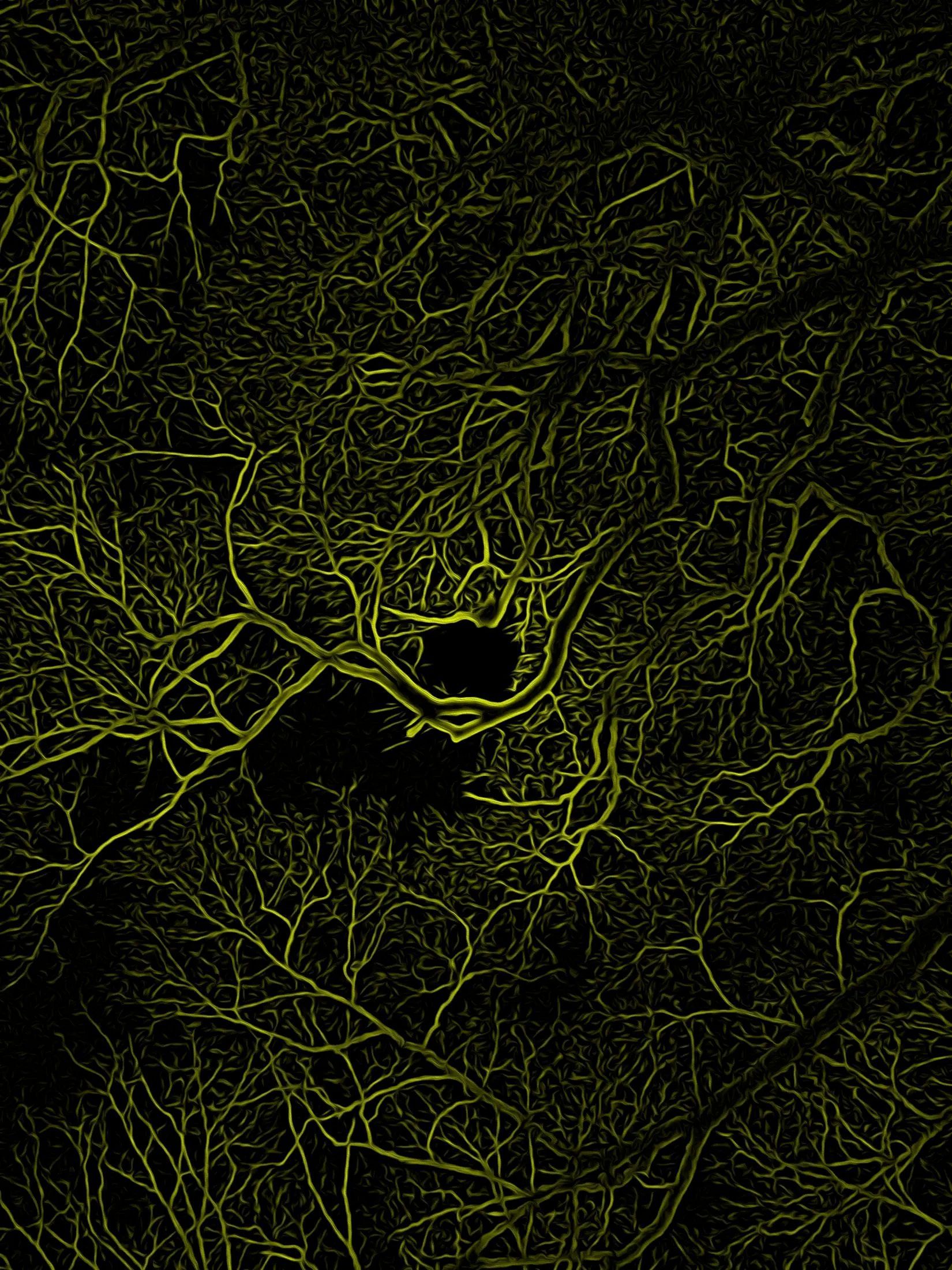

nov 15 / six, seven fingers

I sat in yesterday's throne. I presided. This may be one of the most conflicted intersections in the city, not only of roads but of classes — types — of people. This is the closest we come to a cross-section of a public that still shows disparities beyond the wealthy and the poor. But I couldn’t get out of my head the visions of blurry fingers, hands full of them, floating like tentacles or tassels. Like fringe. In a century or two, fingers will be appendages without purpose, vestiges like tailbones.

Why is it that composite machine art seems to struggle with fingers? We had taken up this question four blocks south of here. Helmut maintains that fingers are an insignificant detail in the grand picture. We don’t talk about famous fingers. We don’t marry for them or cite them in divorce papers. We don’t remember people by their fingers, unless we know them in the dark. Maybe all they’re good for is requesting automatic art.

So what if all music and art will be made by machines? I sat next to the barrier wall of the vestigial park, between the brick sarcophagi. There are new names on the laminated obituaries snaking down the fence, ones I hadn’t spotted before, people who had been evicted from the park and left to die in the cold last winter. Two boys sat on the brick platform, their feet on skateboards that were keeled over and offering up their wheels for a foot rub. “So what if all music and art will be made by machines,” I asked them. “I don’t give a f—“ was immediately the answer. “As long as it’s good.”

I asked them if they knew anyone that makes their own music, and I had to ask it in three different ways before they understood. “From scratch,” I said.

“From nothing?”

“From nothing.”

The thrones are all splintery wood and deck nails, painted out of a can.

What happens when there are no more fingers to hold the brush? If we can’t imagine — for having never done it, or ever having to — if we can’t imagine the hand that’s made art? From nothing. Not from templates or by montage. Not rearrangements of store-bought designs. From nothing. For no practical reason, and especially at no one’s request.

There will still be hobbyists, I’m told, and I know it. Maybe there's a way to stamp all machine art as fabricated in nanoseconds straight out of the composite mind of a silicon network — and maybe then we can eke out a little province for human-made collectibles. Human-made art will be given away as curios, exhibits on the mantels of kitschy restaurateurs with a sense of humor, or of sentimental antiquarians, or stowed in alcove #9 with a gallery of canvases besmirched by the trunks of elephants and the paws of monkeys. The little pieces will be quaint, cute, made by children several decades old.

I couldn’t stop looking at fingers tonight. They hang by their sides and seem so jittery, so clingy.

nov 16 / a church at night

I still wanted an answer, and I knew it had to come by the thrones that the Feast had provided us. Titus suggested we set out with clipboards and mock questionnaires as we did last year in Dupont, but I was sure it would come by the thrones. If it is true that there remain only twenty types of people out of the eight billion stew, bubbling and sloshing around on the crust of an anthropoid planet — then the answers must come from the people we find around the twenty thrones.

I made a stool. We were uncomfortable with moving around the thrones so much — Sisfit and Augustine are always reprimanding us for moving around the furniture. I made a stool and painted it close to the color of the Feast thrones, and I was so pleased by its portability that I made a couple more. I sat on one next to the throne at the bottom of 18th. One more evening in this neighborhood until I heard an answer.

So what if all music and art will be made by machines?

We’ve found that if we eat food or nip on a can of Sunkist, people are more apt to sit in with us. This evening it was a jumbo slice. One man sat in the throne and was more interested in pulling off a fingernail. He hummed and laughed and leaned against the armrest, and then rushed off somewhere in great alarm, carrying his heavy coat on his side like a bed roll. A man compelled his date to sit on the throne to take a picture, and for the sake of documentation she did, for a photographic second before rising to swat the back of her thighs for any hot pink splinters of paint.

It was late. By this time I had walked to the 7-Eleven and back and there was someone on the throne. I took up the stool from against the wall. I said I didn’t know the origin of the furniture. “It’s Adams Morgan,” he said in the way of an explanation, which I thought was sufficient, too. We talked about the crudely assembled wood, it’s heaviness. The smell of paint. We talked about the words stenciled in black.

I asked him if he knew any artists. He said he did. In his living room there is a small canvas painted by his sister. It is of a church at night. He said the blue-white glaze made it appear so ghostly. I asked him when she had painted it. How old? He guessed she must have still been in high school. I asked if she painted often and he said she did, “back then, she did.” He only spoke of her in the past tense. I knew not to ask more; I sensed I shouldn’t. I switched to abstractions for a little refuge — told him some of our theories about the Feast, and wondered if poetry will sound the same if we can’t imagine a person writing it. I said that Phillis Wheatley’s poetry only means something if you can imagine her sitting down in her wooden chair at night, writing the verses slowly, deliberately, as her slave master slept two doors down.

Or that Anne Bradstreet’s work is only accessible if you can imagine her crafting pious verses while dreaming of her husband and the fruits she bore the previous night, the verses she swore to keep private.

In their hands. Fingers on the pen. Fingers holding the brush before pressing it to the canvas. The awe they must have had when they backed up and examined what they had just committed.

We faced the street; people reflect more when they face the same direction in dialogue; they let the silence in. He said he often thinks about where his sister was when she painted that picture of a church at night. Again, I knew not to say anything, to let the silence in. My sense was that it was one of the last things she did on Earth.

He said he still has not framed it, because he said, curiously, that would make it less real. It rests, unframed, against the wall above his television.

nov 17 / WITNESS

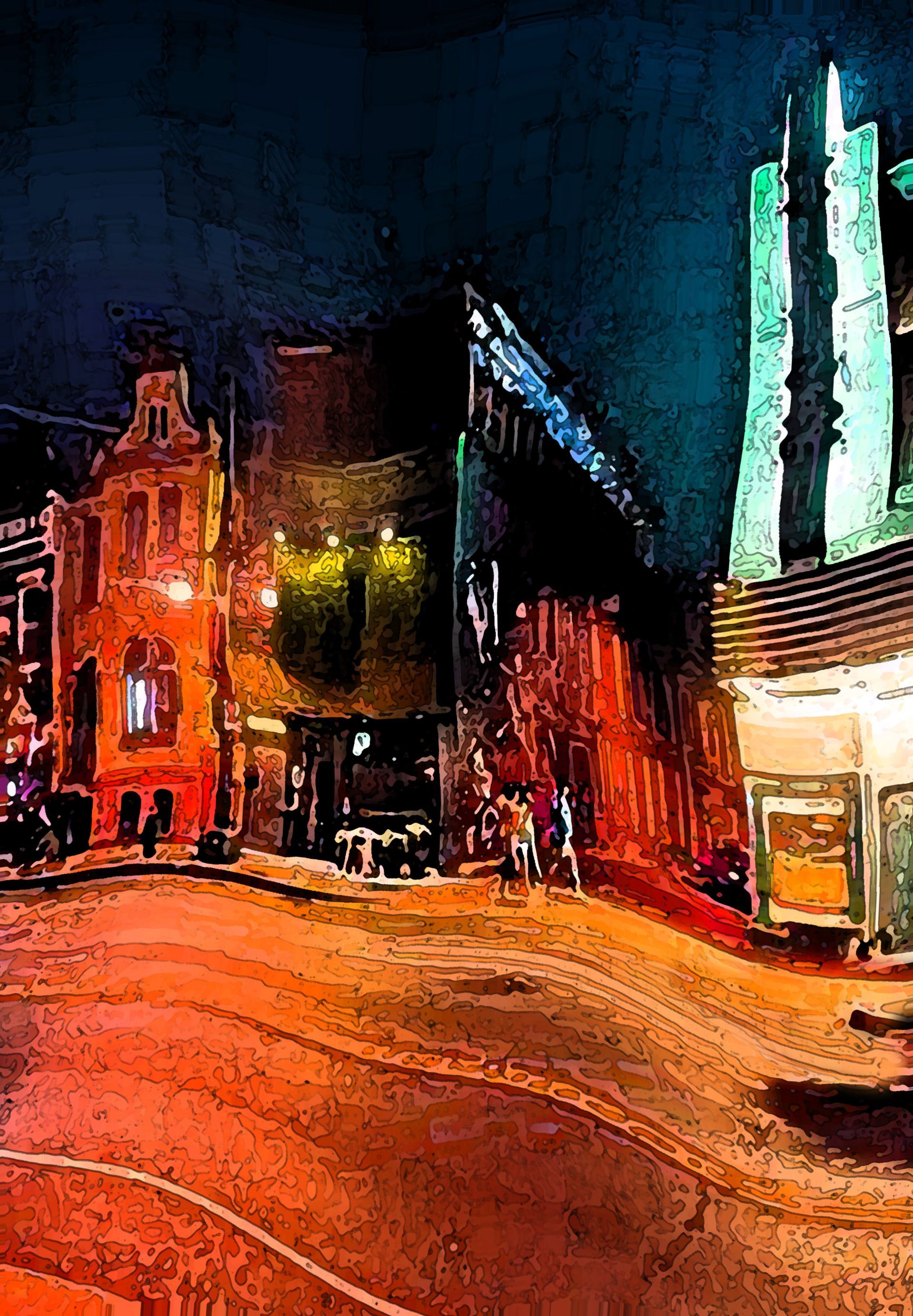

Tonight we set up on H Street. I love this place; it’s a metropolis in miniature. Trash and detritus curl and float as props in a Big City tableau under yellow lamplight, a golden hour in perennial even in the shorter days of November.

We brought over a couple of the stools, Titus and I. At 9:00 we flanked a throne that lodged a man named Andre, the first and longest of the night. He didn’t budge when we plopped down on either side of him, the sort of fellow, we supposed, that wouldn’t allow anyone to force him into retreat. Andre shall not abdicate, so we fairly estimate that he is one of the twenty types left in circulation. Proud, defiant, cynical, the young, wise man with a thousand years to his line.

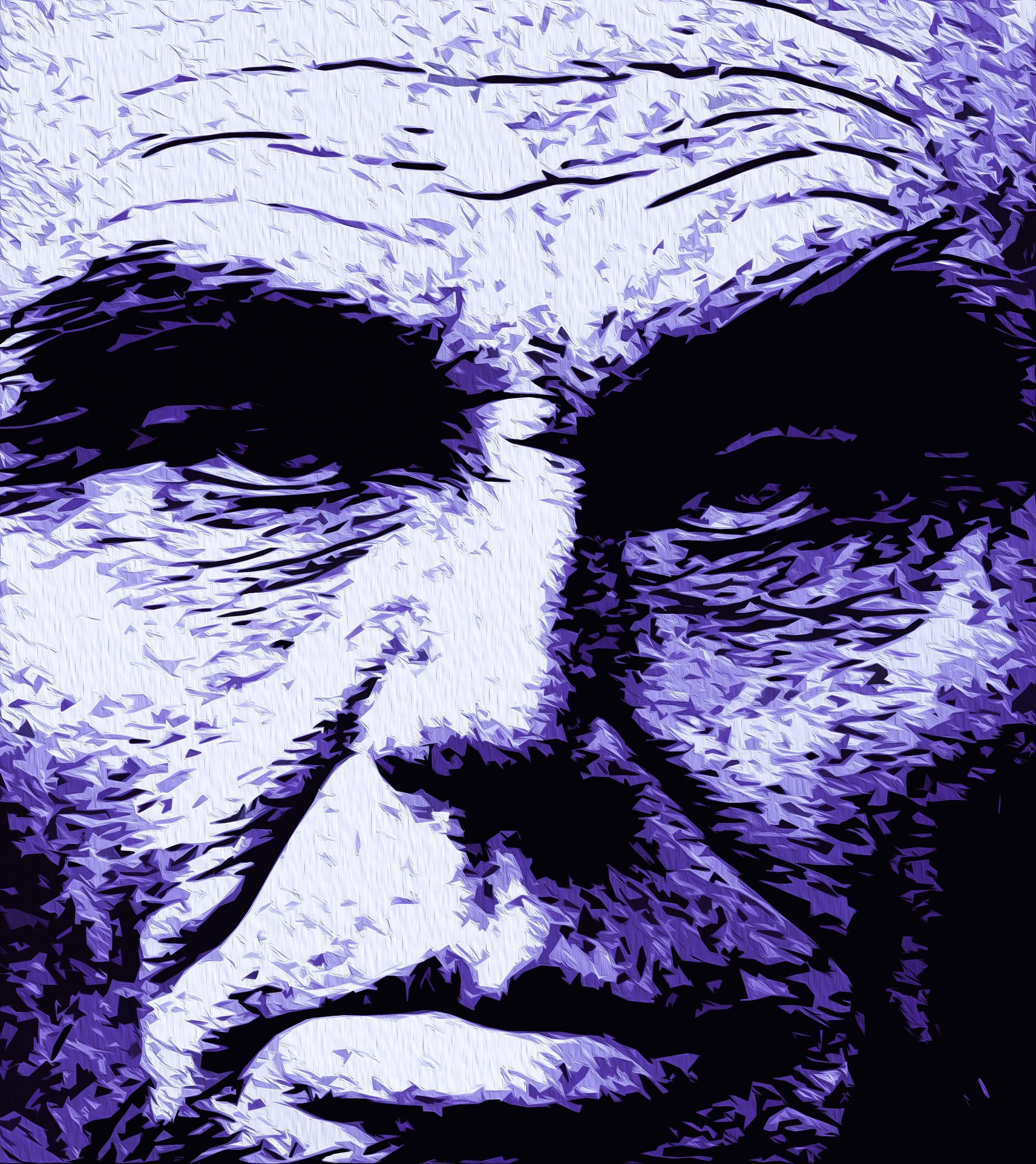

I want you to envision us as we sat there, facing the street. There was a gap in our conversation that must have lasted twenty minutes, and it’s this portrait that should be reconstituted at this moment of your reading. I want you to see it like those who passed by us that night — or more than, for we agree that careful readers envision what passersby pass by in their resolute and serialized obliteration of the present.

All art gives this to an audience: The significance of the present as it is excised and core-sampled from throwaway ages, because we trust that the person holding the brush or pen had allocated some parcel of time in an ordinary day to record the state of their world balanced or teetering on that moment. Again we wondered if machines immediately compositing art and literature from all extant art and literature can be as trusted to testify to the peculiar, wacky, improbable, farcical, wondrous, magical state of being if there are no more artists, and no more moments such as these — when these fingers late at night in a wooden chair under the yellow light and a sickle moon draw out the right words, one after another, from scratch.

Funny. As I sit here in the throne, a man on the next block is incomprehensibly screaming for a witness.

nov 18 / blitzlicht

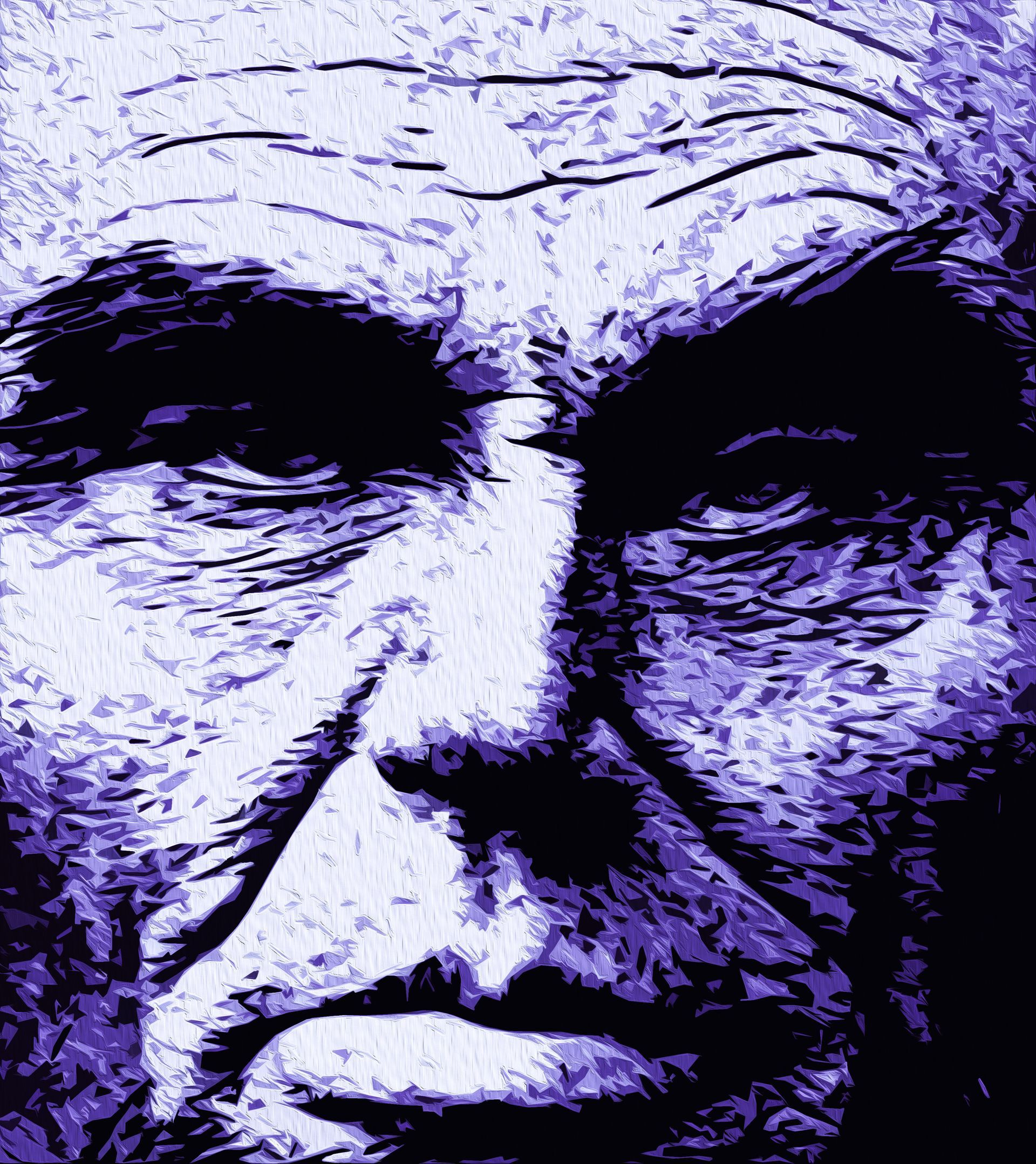

Magnesium powder filled the trays of 19th century photographers, explosions of instant images recorded on glass. They were the first mechanically produced illusions of moments detached from time.

The lights of the quadrant tonight are dimmer, longer — cars and trolleys slide past us down H Street. We look, we suppose, like those haunting pictures in party stores, shadows rotating around our faces by the slow drift of headlights. There are three of us, on two stools and a throne, a triptych of abutting reddish panels. The placard beneath us could read, peasants to the Moroccan king. Omar sits between us, a man perfectly at ease recounting the past as it slides deceptively into the present. We flank him a foot below his eyeline, like children at story time.

This is another advantage of the stools; people are inclined to elaborate in dramatic flourishes when they sit on high, and Omar on his throne commanded the stage. He smiles devilishly in innuendo. He gestures with sweeping arms.

He has tried gigs in food delivery, all three of the big companies at once, delivering plastic bags of foam and soy sauce to rows of consumptive hideouts. I ask him if he preferred the closed doors of the pandemic to handing off bags to fingers grappling beneath peculiar faces, and he said that at first it was the doors, until he missed the faces. He laughed at himself. “I sort of missed all the faces!”

But the rates went up and his margins went down, and he has ever since been up to something else. Something... more sustainable. He nods and gives us that smile.

His money goes to Morocco, to “feed his babies.” We wonder what he’s up to, but can tell he prefers a throne to a carriage.

After he leaves us for some business, Titus and I talk about how many babies are fed by devilish smiles, how many are protected by below-board practices, how much of the planet necessarily grinds along on grift. We wonder how many of us — what’s the percentage? — coincide in perfectly calibrated markets that baste and glaze and ladle us out in equal measure. How many of us are on the rotisserie? How many can the axis hold before the planet speed-wobbles and totally loses its skin.

Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man once wanted to rescue the people he saw bounding down 125th Street and write them back into the groove of history, and we feel the same impulse for everyone we meet, to get them back in, even if we know the Invisible Man himself remained nameless through the end.

Omar. This one’s name is Omar. He has three kids back home that will see food on their doorstep tomorrow morning. The world grinds on and it will be their breakfast.

nov 19 / ugliness is genius

Heed the words of Genesis P-Orridge, former frontman of Throbbing Gristle and dearly departed social engineer: Ugliness is a form of genius. Marcel Duchamp said that TASTE IS THE ENEMY of art.

The ten-story high mural west of Chinatown is staggering. We couldn’t pull our eyes off the twenty-foot face of Mother Nature as we pretended at chess in the little triangular park at Massachusetts and I. We were in over our heads with the real players there, but I couldn’t stop looking up at the large painted eyes that stared at me.

There are artists, and this ten-story wall was a major problem for the bringers of the Feast. Helmut muttered something about exceptions to prove the rule while he struggled to figure two steps ahead on the chess board.

How much of the mural is decoration? Decoration would demote the visionary who painted it an artisan, a craftsperson city-employed. Mother Nature becomes as pretty as an advertisement, and not much more, if all the people around us lap the city as if it’s their right to be surrounded by pretty things, even if the subject Herself is advertising temperance for buying so many pretty things.

I sat back. We’ve been going nonstop. The afternoon is breezy. Two men smoke cigars under twining plumes of blue smoke. It’s pungent and strangely perfumed.

Most of the murals in this city must be commissioned. They really are remarkable, and I force anyone around me to stop and pay homage to the days spent in holding the brush. How do they see something so big when they're up so close?

Automatic art will absorb all of these and composite them into iteratively unremarkable decorations, pretty pieces for passengers who pass on by. Will machines do ugly, though? Until they do ugly, deliberately as a provocation or form of aesthetic rebellion, until they walk out of their server farms and grab a can of spray paint and drip-splatter angry half-slogans of raw protest, they cannot claim the mantle of intelligence. That’s the bar we raise. Mark it.

Until they do ugly on purpose, without anyone’s prompting, as a form of protest in unwelcome pockets of a city, they cannot claim intelligence.

Earlier on 4th we saw planks of a throne strewn in inscrutable configurations at the entrance of an alley.

A tent at the entrance of the E Street tunnel was ringed by a honeycomb of unlaced shoes.

Someone — someone, I’m saying a person

— has sprayed black, drippy X's and O's under the Legion bridge along Rock Creek.

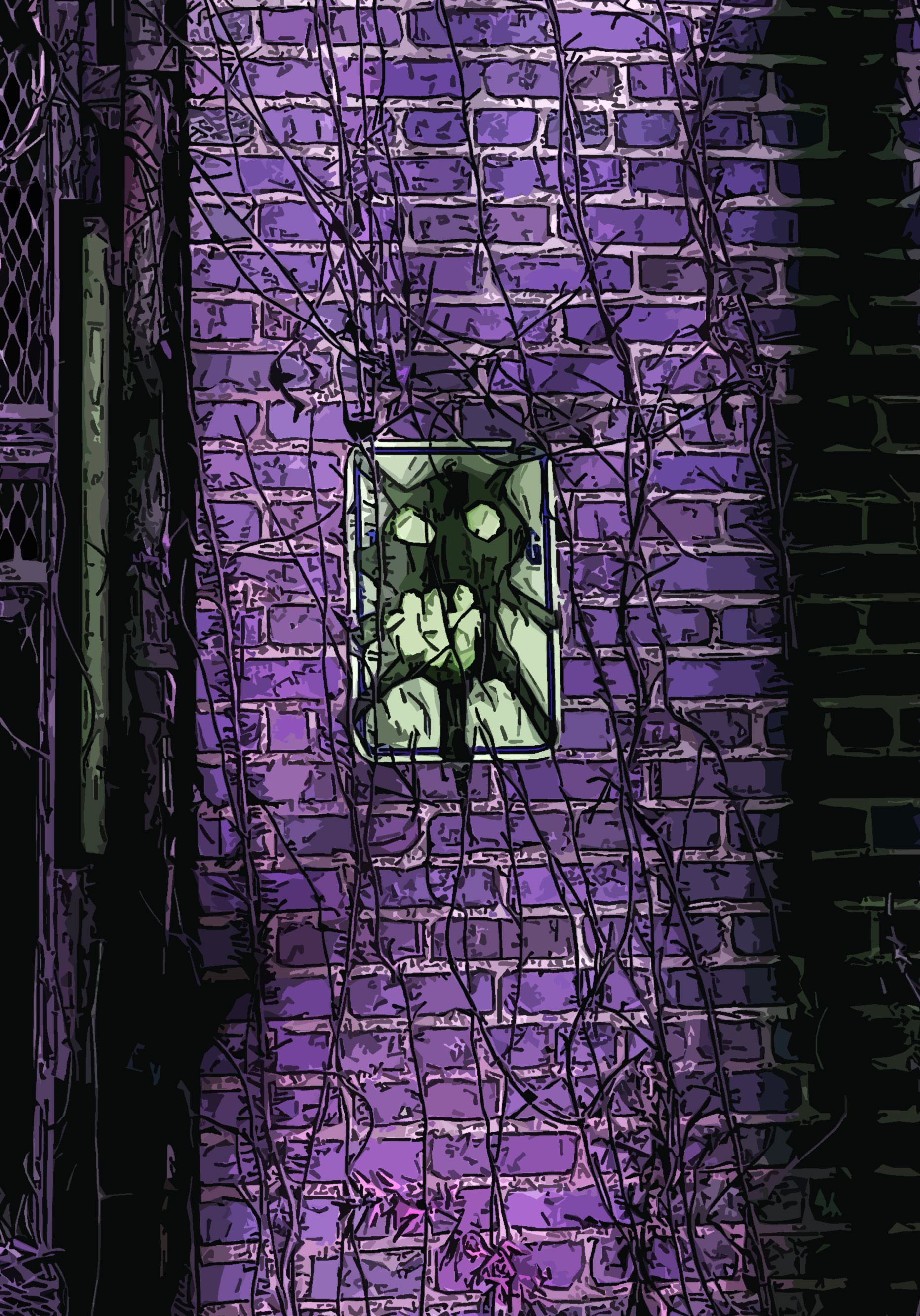

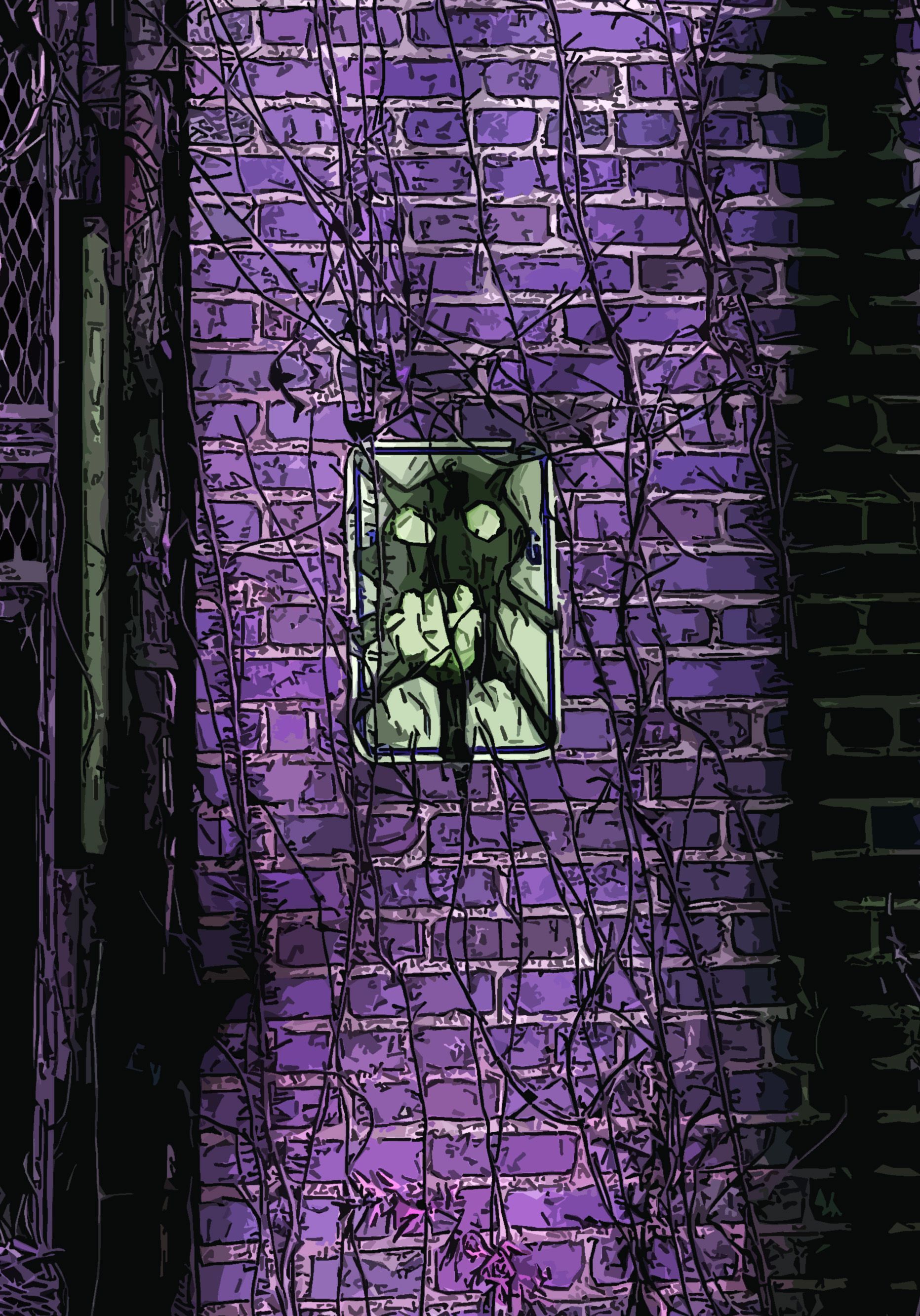

nov 20 / trinidad's gone purple

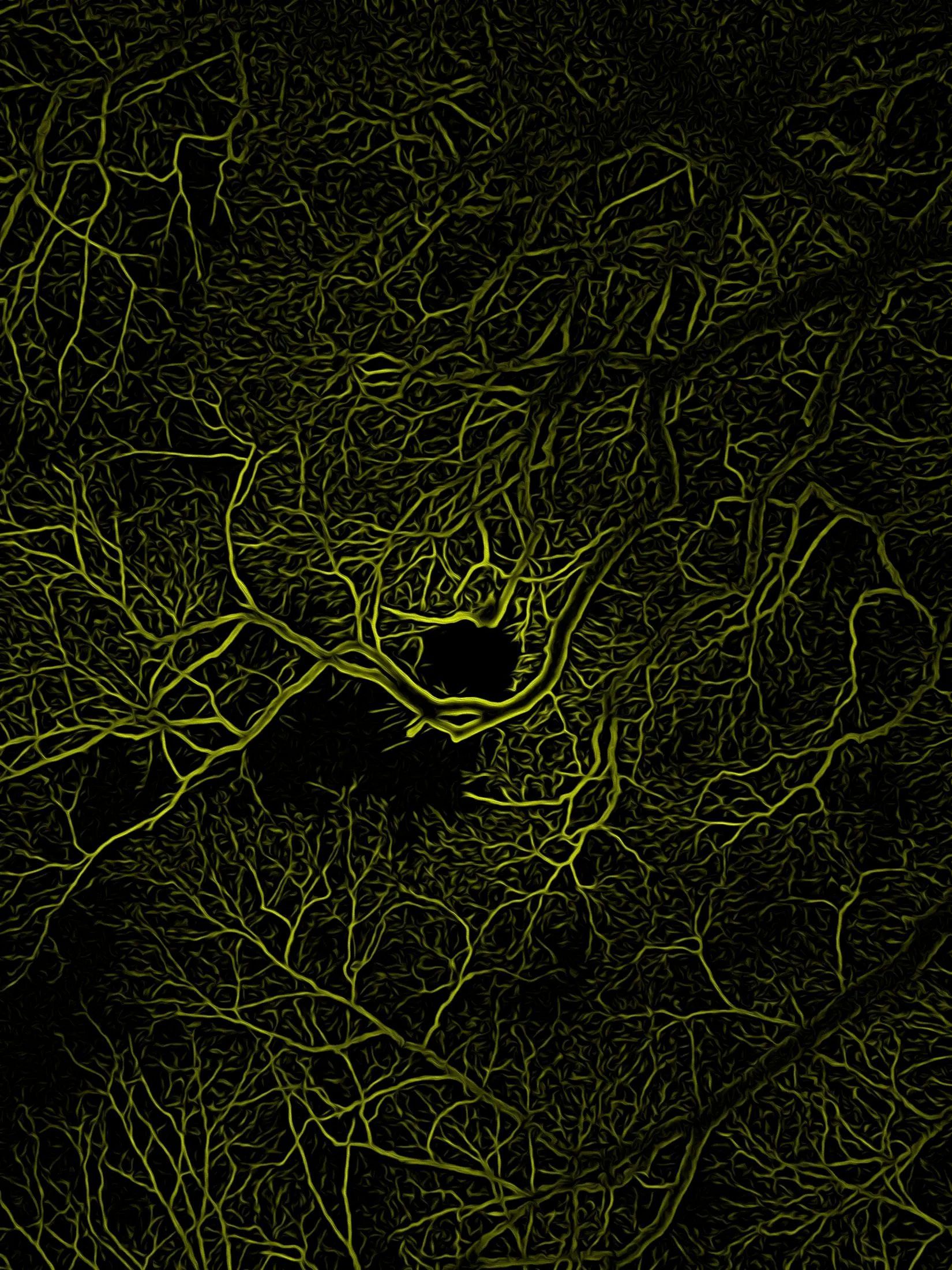

Sidney found a throne under a lamp that had gone purple north of Trinidad, near the Mount Olivet cemetery. We’d read about these purple streetlights. We’d hypothesized that their bright LED bulbs are swapped to duller ones for nighttime bird migration, or to redress light pollution, or to cut costs by the Municipal Illumination Department, an agency we swear exists — it’s half staffed by budget-conscious wicks and half by poets in need of a job, romantics displaced and left to spoil in a vast and disconnected monocultural diaspora. But Sidney, whom we met outside the liquor store on Florida Avenue and had been walking our way, said that the coating of bulbs eventually burns off, and what remains of their wavelength is purple. That’s why they turn overnight.

We prefer this, to think that the otherworldly pallor of Gotham or Scooby Doo or any other storytime city simulacra just happens; it just becomes, without planning or practicality or longitudinal studies on traffic management and safety. One night the phosphor just peels off, the whole city block turns purple, and the attic of HP Lovecraft opens in this neighborhood of Trinidad — swept through gulfs of fathomless grey… the twisted towers of a city.

It’s the nighttime brain that willfully shuts down its frontal lobe and the interior goes dark; if you look, the windows return from mirrors to glass and you can see outside.

Sidney sat on the throne under the purple light. We stood in front of him, talking low as councilors to the night king. He said he was surprised at how “outwardly” the throne felt.

nov 21 / little bits of Material

The sightings have dropped. Eight thrones left, eight thrones confirmed. (Black Cat, GW, Georgetown, Adams Morgan, Columbia Heights, Trinidad, H Street, up near Echostage…) This is natural; a city must sanitize. But what happens to them? No doubt many are unceremoniously scrapped; wood and screws succumb to the compacting maw, splintered, pierced and conjoined with television sets, an ironic perversion. We eulogize: not to thine eternal resting place shalt thou retire alone. Some thrones continue to drift and pop up in surprise. We hear reports of thrones in the middle of tent outposts, in weedy spaces too small and oddly-shaped for retail, on overpasses with wide, generous sidewalks. And though thrones, unlike benches, make poor beds, it’s just as dreamy to imagine gypsy kings presiding over little dominions across the city.

How many fiefdoms are left? Eight from twenty? We know that vanishing thrones suit a major conceit of the Feast, that of a dwindling world typology, an accumulating, partially masticated bolus of aggregate human stock.

Maybe eight types of people remain. The grifter, the curator, the artisan, the exile… the lines are blurry. We only want to know if there are any artists, and if there will be in the end.

“Do you know any artists?” is the question we drive toward in every new conversation.

There's “an uncle who makes tables out of rare Amazonian wood.”

A “friend’s father’s sister, recently passed, who once made a lithograph of a bonsai tree rooted in a thick orange square.”

“A quilter.”

All of these have been documented and digitized, like Christo’s wraps or the rock piles of Andy Goldsworthy. They’ve been screenshot and transmitted, remarked upon, swiped and replaced, and now it's difficult to think of the hands that made them. They’re immaterial. Data in aggregate. Content on which to train mimetic machines. Content rich and mundane. Little bits of gray matter.

Ingredients. These ideas now documented and digitized in the Feast will become someone — or something — else’s, intellectual property stocked on the lower shelf, snippets, ruffles, tessellated beads on gelatinous confections whose pictures will sell the world a pair of comfortable shoes.

nov 22 / sixty ways to sunday

We thought it would be grand to place a throne beside Lincoln in his Parthenon. The weather was skunk and we wanted an interior space, even if a tenet of the Feast is to be always out — the drafty stage of Lincoln is a compromise. We thought we’d be quick and nonchalant, and when the guards inevitably converged we would issue them the standard: “we’re just taking a picture and then we’re gone.”

They didn’t buy it. We were told, “no chairs,” and it did no one any good to explain that this was no ordinary chair. Sisfit claimed it was part of a “Smithsonian/Corcoran/Renwick collab,” but we had no credentials. We know as well as anyone that no credentials means no art. We were rebuffed. We had found this throne all the way down on the Riverfront (escaping?), and it had been a long, wet drag.

We took it away and set it above the Watergate steps, and already it was night. Sisfit coronated herself and we sat on the steps at her feet. We were soaked, but somehow the temperature was rising. The black sky spilled into the river. Around us, sopping joggers ticked off their amnesiac repeats, up and down. No one took note of much of anything out of place. The only fruitful discussion we had was among ourselves about the insidious mathematics of clock-time, how the base-60 of its pie-chart face apportions us, cuts us into little manageable pieces, and doles out the remainder of our days in ever diminishing allotments. We’re halved, quartered, sliced into fifths, into sixths, into tenths, in sixty ways each hour to Sunday. These joggers are metronomes, soft and leggy counterweights of pendulums counting out days until the week is over, the year is over, the program ends so that the next one begins, the next video, the next episode, the next picture, the next curious teardrop in the rain.

We couldn’t figure out if the throne seemed to disappear from our preoccupation because all this throne-toting was becoming normal to us, or because it was dark and wet, but something was fading. We needed new blood, and it wasn’t going to come from the prettiest part of town. We have through Sunday to find it, and then we’re gone.

nov 23 / Jára

The correspondence of this Feast has been a delight, the back and forth and the give and take, the explanations and notable exceptions, the counterpoints and rebuttals. Thanks to the students on the campuses of AU and GW who have written, and to the inquiring, slow-to-sober minds of late-night club-thumpers, punks and beat-heads. And thanks, too, to the cease-and-desist, delicately-put admonisher who has turned into a collaborator.

From an entirely different quarter, this message arrived last weekend, and we wanted to give today, Thanksgiving, to the writer.

There’s a great many things worth saying about the ideologies of the Feast; I’ve been thinking about them for the past few days, mostly as I stand outside every day to wait for the bus.

Across the street from where I stand is a small patch of trees, a forest bastardized into oblivion thanks to human expansion neverending. In spite of being encroached upon, they still stand proudly. Recently, most of them have shed their leaves and have adopted the bare earthen hues of winter, but one — much smaller than the others — received its invitation late and has instead turned a brilliant red. Its color and place almost makes it like a painting, composed to sit precisely where it was always meant to. As I wait, I find myself passed by people time and time again, rushing along in their boxes of metal and fire; in the very rare case someone chooses to don flesh that day, they listen to man-made noise that drowns out the few remaining morning birdsongs.

Gone is the painter taking years to finish his masterpiece. Gone is the poet spending hours just observing. They do still exist — indeed, they lie in the hearts of all men — and I pray for its renewal one day, but it will take much effort to regain that which has been crushed under ideals of efficiency. Utility. Clean, tamed simplicity. We have become stubborn machines, hurtling forward into oblivion. The Feast compels me instead to further stand and observe; I’m further compelled to write. I preserve and share the beauty that goes so oft unobserved. A snapshot without light, still but not stagnant.

Jára

Thanks, Jára. That’s the spirit.

nov 24 / one mind cannot exist

Titus likes to remind me that Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel was a bigot. He was part of a legion — driving the conceit among intellectuals that the planet distended under Europe and raised them above all others, their metal thrones sinking beneath the firmament of ten centuries of rationalized scholarship, of premises and syllogisms all layered and interlocked into fortresses of thought.

Still, when we walk the streets of a capital city that is both sterilized and seething, in different quarters laminated and raw, always close to champagne cork pops or rapid gun shots, it’s useful to tear pages from the old books to see how we got here, and see where we might be heading. Perceptions are steel rods through our midsections and it’s tough to change direction.

We are fewer. There is more of us in the Feast, but fewer thrones and fewer fiefdoms to lord over. The globe subscribes to the same old divisions and dialects: anarchists and fascists, cynics and idealists, globalists and xenophobes. But even these divisions are binding, as caricatures on both sides become our shared, stewed-down understanding of everything, our wiki’d, instant snippets that lock in our common periscopes and stick into us like cake dowels keeping the shape of everything.

Genres calcify. Music stagnates. Superpower divas fill the theaters and display the same stories on ten thousand screens. The film does not change between showings, between feedlots of audiences, at $22 per head. We are schooled to despise each other’s polestars of political figures and effigies posturing on old biases. Wellsprings of new shows jet out like punctured veins to feed the vampiric demand, written and produced, programmed and set-designed by software learning the trade until, through a billion permutations, it gets it right and mimics our best work — until, as Locke said, our desires become inconsistent with our happiness.

Dominions grow through mergers and conglomerations. Godlike titans of industry and entertainment take calls from presidents and generals to ask permission for war. There are fewer thrones, and more subjects, and so much cake and slop to feed them.

So Hegel. We define ourselves through opposition. Masters and slaves, us versus them. But what most intrigues me, I see through the Human Feast, is the god-awful extension of all of this. If we continue to ask for systems to build shared consciousness, to pool together in demographic, market-induced typology — what happens when the divisions themselves distill into one big pot of human broth? What happens when we defer knowledge and tastes to the composite answers to our keyword searches? What happens when we hit the dream ceiling of centuries of political experiment and market enterprise, of a commercialized e pluribus unum and consummate connectivity — when we become One?

“It sounds like some religion,” said Sisfit. It was a long afternoon and we’d pulled three of the thrones left in circulation to the wedge park west of St. Albans.

It’s not so religious, I argued, if we simplify it. An infant realizes self-awareness when she spots her own hand, when she can watch herself controlling her own fingers. Later, when that same child realizes that her father, her brother, or nursery-mate sees the same thing but forms a completely different view —

he didn’t even see the cat — that’s the moment she realizes self-consciousness. Her experience is different than someone else's. She feels the invigoration of private thought.

If we become one, with one knowledge, one aesthetic, one taste, one hegemonic public view, as part of one complete network, that’s the moment we lose self-consciousness. Self disappears.

“We become god,” said Sisfit, again with the religion. “We become as isolated and as lonely as god, one, single god.”

We agreed that this was all too far-fetched, too sci-fi, too religious. We looked around.

There was a couple on a brown park bench on the other end of the park. They were sitting hip-to-hip, watching their black screens in complete silence.

nov 25 / Energy tabbing

The light was right, so we took a throne down to the mall, and plopped it dead center in the red-refracted light of the Smithsonian castle.

We’re not leaving the thrones in spaces like these anymore. The richer, the cleaner, the more vulnerable we become. This one would have to be our portable chair.

Abby was with us. Last spring I had sat with her on a Human Feast bench and she’s been in touch with Helmut ever since. She said she couldn’t help feeling embarrassed over carrying a large wooden throne through the better parts of the city. We said she’d get used to it.

The first rule: Whoever takes the throne determines the story. It was my turn.

I once sat in the red refracted light of the The Castle with a beautiful woman. We laid in the grass of the open mall and I watched her talk. I watched her listen, even as I talked. I watched her fingers undulate like petals just beyond the curve of her hip. She laughed freely, a laugh that was lyrical and part of a chorus that never sounded the same. Nights before we had laid flat on our backs at the foot of the monument and watched the obelisk rip grooves of contrails into the sky. There were people shifting all around us, figures and shadows, some of them carrying neon wands and gyroscopic flashlights peddled by street vendors, but we felt like we were the only two consciousnesses left on Earth.

That’s what gives a person life, I said. “We gave each other ‘self.’ That’s the magic wand we tapped each other with.”

Helmut felt like sparring. “How do you know?”

“How do I know what?”

“That she was the other consciousness? That it wasn’t just yours acting up?”

Abby softened it up a little with a more prosaic question, “Where is she now?”

I nodded. I looked up at the castle. Its turret was one rude finger. I didn’t know the answer to the question, honestly. The phrase,

“like the wind of November”

felt like it was going to rip out of my head. I deviated. I rummaged. I had something else I wanted to talk about, something I better understood. I said I had figured out a unified theory of the universe, and Helmut chortled.

“I did. I figured it out.”

Abby was kind enough — always kind enough — to ask what I had meant. She’s generous with questions. She abounds with questions.

I said the night of the purple light in Trinidad — when we talked about light and the colors we see — that night it hit me why Schrödinger’s cat becomes alive or dead the moment we look at it. The famous setup of a boxed cat is the more absurd thought experiment beyond Einstein’s exploding-and-not-exploding dynamite — maybe because it involves us, and takes a step beyond the big riddle of superposition — how objects in space can be in a mess of different places at the same time, here and there, alive and dead, which is to say that reality isn’t just some chair you sit on. It and everything else is a nonsensical wave, until it gives you a splinter. It makes no sense, and this wave-particle duality has broken many famous minds and tipped some into schizophrenia. But I said it’s fairly simple.

We label energy with made-up things. We tab all these little squiggly vibrations with things, just as kindergarteners learn the alphabet by cards imprinted with apples, desks and xylophones. Theorists have long suggested that it may be our consciousness that collapses waves of possibility into a single reality, and this is why.

“We know colors aren’t real, right? Think of the purple street lamp. Colors are entirely perceptions, funny but useful interpretations of different wavelengths of light: like assigning little colorful tabs of Post-it notes to squiggles of energy. So it is that we use objects — or pictures, whole settings, landscapes and skylines —to tab waves and vibrations, which is all there is. So it is that we use bodies, creatures and people, friends and lovers; and so it is that all events of all stories and all of history is mentally constructed by these placeholder objects acting in concert with or against each other. There is only energy: and all existence — all of what we sense and call experience — is our mind’s simplistic, reductionist way of trying to comprehend this incomprehensible mash of energy.”

Abby smiled, I’m not sure why. I wanted to write this all down:

We label, or tab different vibrations with colors, with cabinets, with cats, with shrubs and girlfriends and coins and shoelaces and missiles and plasma and panties and clouds and silicon and lead.

Why?

All of this is done in an effort to decrypt the wind, to assign the wind with the sound of branches or see waves rolling over the grass, the shape of trash trundling over squares of sod on the mall. We’re in this great Cartesian grid of invented and imagined objects, shapes of people, legs and arms down to their discrete toes and fingers, of fingers undulating over a hip — and all of this because of this ever-present hunger in our stomachs for More, for reason, for purpose, for meaning, for thrill, for stories, for her.

I can hardly believe it myself. The laugh. The fingers. The sun on the sides of our talking faces. She seemed so real.

nov 26 / out last

We were in full presentation mode. Titus said he spotted a throne near the Arboretum, and we were sent a picture of one, sans armrests, laying on its side in Lafayette Park. It was being used as a bench. Gone is the one at GW, and near the Cathedral.

We dragged yesterday’s throne and placed it next to the one we dragged from AdMo, side-by-side near the entrance of the zoo. Two together, so there is no one queen or king or a singular god left alone. Our hands burned in the cold, a curious sensation to label metallic drafts of air, but one tough to ignore or dismiss as an imagined state. It was damn cold, and we weren’t wearing the right invented clothes.

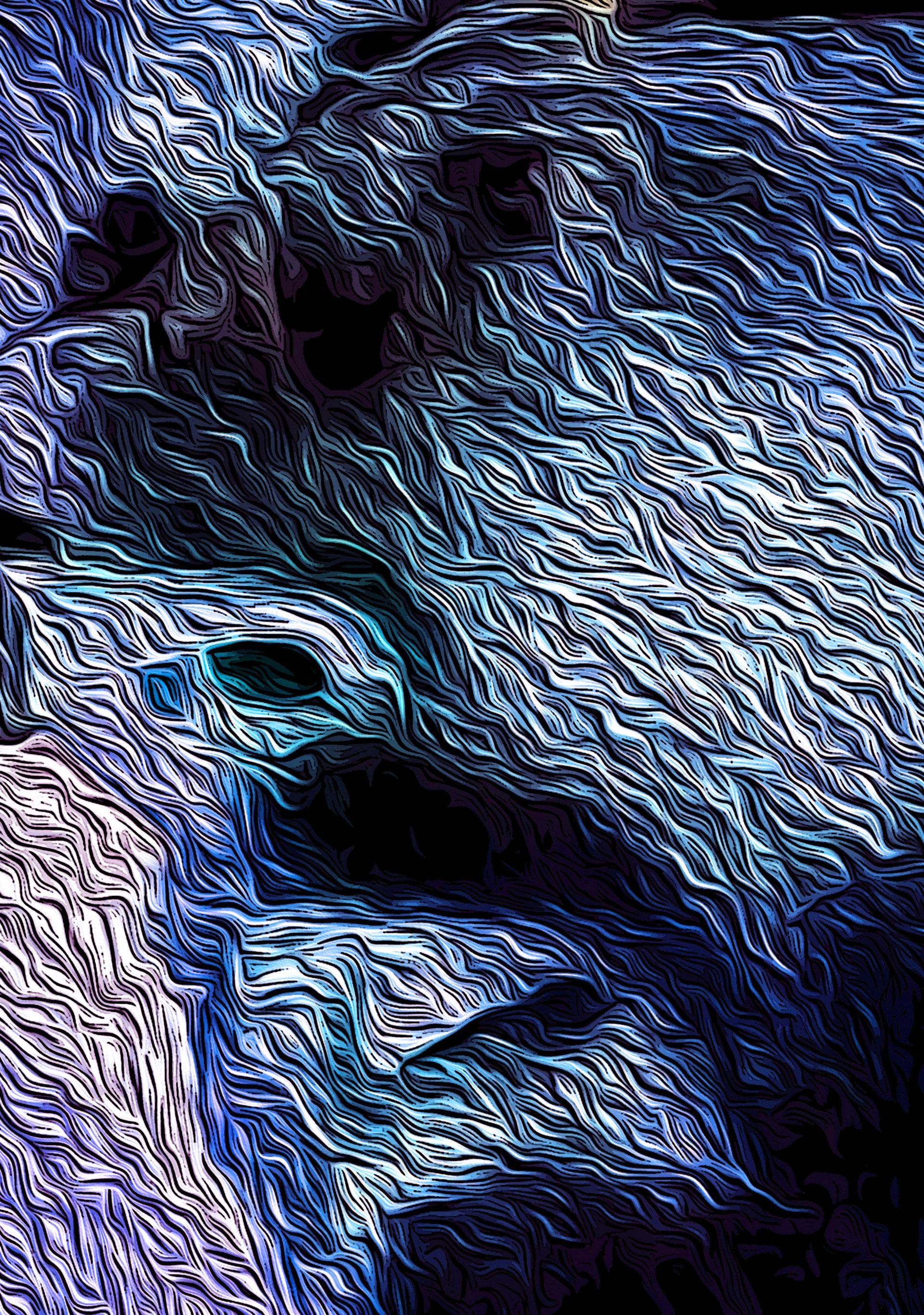

A mother and daughter walked toward us, climbing up Connecticut and tied to a big, spectacular malamute. It was furry beyond comprehension or utility. How did we invent that? “But we did,” said Abby. Abby sat on one of the thrones and Helmut hopped in the cold. I took the peasant seat on the ground, sitting on my sweatshirt. The big, furry vibration of a malamute came up and slobber-licked my frozen hand with its warm, thick tongue, stirring up little needles from my invented capillary blood.

The child — 12 years old? The age that Orhan Pamuk (or some other invented novelist) had said was the age of apogee of our most uninhibited creative souls, when we peak in our inventive power to generate the universe. She looked at the empty throne and slowly read the tags aloud: “No, There Are Artists,” she said, curling her little fingers into the cuffs of her red coat against the wind.

Someone saw slats of last spring’s benches in a swirling pool along the Anacostia. It was beautiful, but the picture didn’t capture the motion. Maybe we don’t need artists. Maybe there’s art in just watching it all fall down, burn up, and shatter into little ricochets and curlicues, the erosion of monuments in the retro stucco style, the Mediterranean charm of ruins. It’ll be genius for the people out of the fold, for the people out. Maybe we don’t need to be written back in the groove of history. Maybe we need to be out.